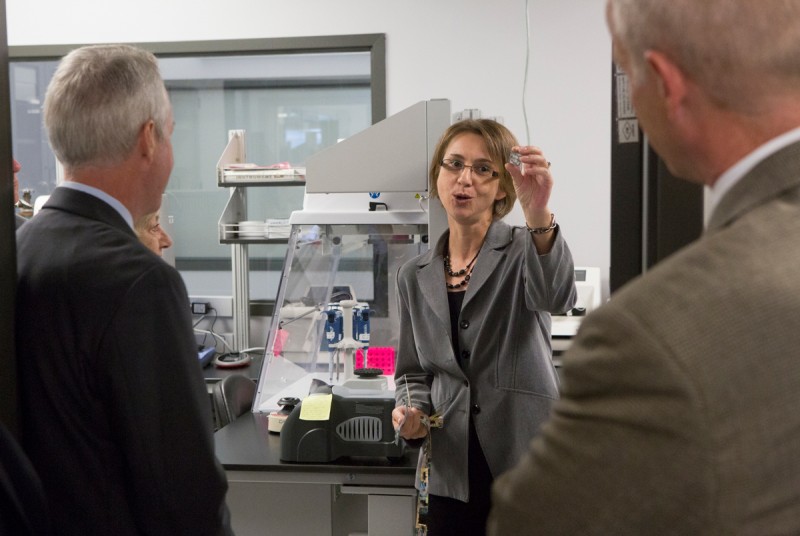

Sauer discusses biofilms at Dean’s Distinguished Lecture

Disarming Biofilms — How to Turn a Microbe Against Itself

Biologist Karin Sauer delivered a promising sketch of Binghamton University research related to biofilms Nov. 16 during the Harpur College Dean’s Distinguished Lecture.

During her talk, titled “Disarming Biofilms — How to Turn a Microbe Against Itself,” Sauer shared some common misconceptions about bacteria, chief among them the idea that bacteria are independent — “born to be wild,” as it were. Instead, she said, bacteria in nature often exist in communities. And these communities are called biofilms.

You may know these “communities” as slime, a bit of scum in a pipe or on top of a pond. But they’re complex structures, ranging from microscopically thin to large, colorful formations that lend beauty to the springs at Yellowstone National Park. And they’re not hard to find much closer to home: “You get up close and personal with biofilms every day when you brush your teeth,” Sauer said.

Why do bacteria congregate in this way? Sauer noted that bacteria in a biofilm are up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than they would be on their own.

This resistance creates huge challenges for a variety of industries, most notably healthcare, Sauer said. Biofilms affect about 10 percent of U.S. hospital patients and are responsible for some 100,000 deaths per year. They’re a challenge to anyone who has had a hip replacement, but also to people who wear contact lenses.

Sauer and her colleagues aim to find a way to break up these communities of bacteria. And they are deathly serious about this pursuit: “When you’re ready to go into battle,” she said, “you need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of your enemies.”

One major weakness the Binghamton team has worked to exploit is the finding that biofilm formation is a developmental process. If it’s a developmental process, that means it may be regulated. And that, in turn, means it’s possible to prevent them from forming and to make them disperse if they do form.

“We have identified control points that allow us to control how biofilms form and develop over time,” she said. “We can also induce dispersion, meaning we can disaggregate chronic biofilms on site and resolve infections that have persisted for several years.”

Following her talk, Sauer fielded questions about clinical applications as well as possible benefits of biofilms. She noted that the dispersion molecule is the Binghamton breakthrough closest to clinical application, and added that biofilms can indeed be good for your intestinal system.

Karin Sauer, who earned a doctorate in microbiology and biochemistry from Philipps-University and the Max-Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Germany, joined the Binghamton faculty in 2002. She’s now an associate professor of biological sciences.

Biofilms Research in Harpur College

The biofilms research group also includes David Davies, Claudia Marques and Jeffrey Schertzer, who joined the faculty this fall.

The team’s findings have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the field of biofilm research, and their biofilm testing methods are widely used.