Binghamton researchers are looking for the next prednisone

Nursing and pharmacy researchers hope to find a replacement for prednisone with fewer and less-severe side effects. Their recent clinical research study was the University’s first to use drugs on humans.

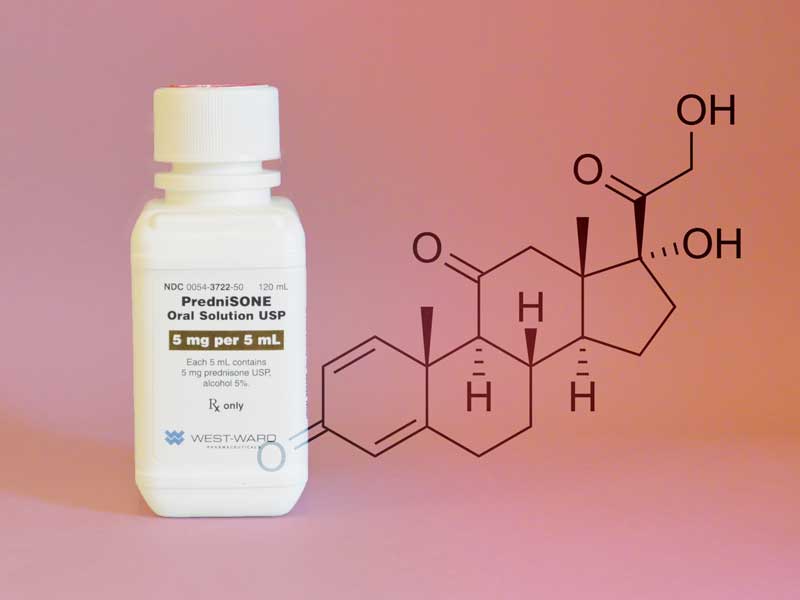

Prednisone — part of the class of drugs known as corticosteroids — is used to treat a wide array of health issues ranging from arthritis, blood disorders, breathing problems and severe allergies to skin diseases, cancer, eye problems and immune system disorders. Common side effects of taking prednisone include sleeplessness, excitement, restlessness, sleep disorders, mood swings, headache, nausea, vomiting, thinning skin and acne.

Binghamton University’s Decker School of Nursing and the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences partnered to find a replacement drug for prednisone and other corticosteroids, which can also cause serious side effects including diabetes, heart attack, obesity and more, most frequently with high doses and prolonged treatment.

In summer 2017, Decker nursing faculty Nicole Rouhana, MS ’95, PhD ’11, and Ann Fronczek, MS ’99, collaborated with Eric Hoffman, professor and associate dean for research at the pharmacy school, on a clinical research study that looked at how humans react to weak doses of prednisone. The study is part of an effort begun eight years ago by Hoffman to find a steroid replacement drug that can stall the progression of muscle degenerative diseases, particularly Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

This was Binghamton University’s first clinical research study using drugs on humans, says Rouhana, director of graduate nursing programs and assistant professor. “We tested a weak dose of prednisone on normal, healthy males and females on campus to see how quickly exosomes — layers of cells/extracellular vesicles released from cells — react to prednisone and start physiological changes such as changes in sleep patterns and hormonal changes.”

Rouhana had the prescriptive authority to order and administer the prednisone prescriptions. Fronczek’s role was to support the research study, overseeing data collection, which included mobile technology assessments.

“The study really needed someone with prescriptive authority, which is why Ann and I got involved,” Rouhana says. “I didn’t know before that anyone could write a prescription for having a bottle of prednisone in an office for research purposes. And I had to write a prescription for each subject. It was a learning experience.”

“Subjects wore a mobile band throughout the study to track physical activity indicators such as heart rate and sleep before, during and after the low dose of prednisone was administered,” says Fronczek, assistant professor of nursing. “The mobile band device worn was similar to a FitBit, but it was paired with a mobile application that had the ability to track the physical activity data at very sensitive levels, not just an average or aggregate like mobile devices are able to provide.”

Developed for Hoffman by Italian collaborators, the app was originally designed to monitor children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

“We worked with 20 subjects — 10 male and 10 female,” Rouhana says. “We brought them in and did a brief health history including reproductive and medication histories as well as height, weight, blood pressure and informed consent.

“We first did a baseline of cortisone and saliva levels and other tests on each subject before they wore the mobile band for seven days,” she adds. “Then they came back in and, based on the individual’s body mass, we delivered nontherapeutic doses of 2 milligrams of prednisone per kilogram of weight and, after one hour, started checking the level of physiological changes every hour for five hours.

“We found that some of the major systems started to develop some changes within 30 minutes,” she says.

The clinical research study had to receive approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) before it was conducted, which Rouhana and Fronczek say was more complex than they originally thought it would be.

“The IRB was extra cautious, but also very open and flexible,” Rouhana says.

“For example, one of the major issues identified in the study was the amount of blood being taken from each participant. We needed a specific process for multiple blood draws that would ease the burden for participants,” Fronczek adds.

Rouhana found the study inspiring. “Many of the subjects were glad to be participating in the University’s very first clinical research study with the pharmacy school, using a drug in humans. Nobody walked away from the study once it started,” she says. “And seeing prednisone’s long-term effect and thinking there might be a drug out there without the side effects — some good will come out of that.”

“It was also challenging when dealing with the subjects who were students because we needed to avoid certain big campus events like Relay for Life and Spring Fling, when they weren’t following their usual routines,” Fronczek says.

“We also had to put on our nurse’s hat on one occasion when we had a subject with high blood pressure who required healthcare-provider follow-up,” Fronczek adds. “As licensed individuals, we could answer many health-related questions and take opportunities to do health teaching and talk more about the study with the subjects.”

“We hope this will lay the groundwork with the pharmacy school and Decker to form a relationship when it comes to clinical research studies using drugs in humans,” Rouhana says.