Searching for cancer therapeutics

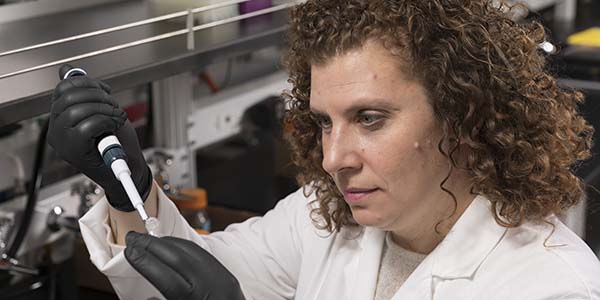

Researcher Tracy Brooks targets proteins to fight cancer

Oncology researcher Tracy Brooks has been delving into anti-cancer therapeutics and drug targets for about two decades now, so when you ask her to explain her research, she can take it down to the basics.

“I focus on funny little DNA structures that can turn proteins related to cancer on or off,” she says. “I do a lot of studying what their shapes looks like – every one is a bit unique – and after I know what the shapes look like and what they do, I can start finding therapeutics to control them and apply them to whatever cancer is relevant.”

Brooks works on two major targets that are important in pancreatic cancer and the broader group of breast cancer, lymphoma and ovarian cancer. “These are high-value druggable targets that people haven’t been able to hit before,” she says. “We’re actually drugging the DNA so you never even make the protein and we get it right at its source.”

But Brooks cautions that, just because a protein is mutated or changed somehow in a cancer, it doesn’t mean that blocking it with a drug will kill the cancer.

“We know a lot of things about describing things that are changed in cancers, but not a lot that says if you decrease it the cancer will die,” she says.

Brooks mentors a number of students who are assisting her in her lab. Some are working on making 3D models of cells and stem-like cells, then knocking down targets in the presence of traditional chemotherapy to see if what they are doing makes the drugs work better. Others are working on colorectal cancer and breast cancer after family members were diagnosed with the diseases.

Brooks understands that motivation. Her grandmother had already beat ovarian cancer, but died from pancreatic cancer when Brooks was a freshman in college. “That kind of got me into the field,” she says, and her focus has remained on cancer, even as she lost her mother to endometrial cancer, saw other family members sickened with one form or another of the disease, and cared for her husband through his battle with testicular cancer.

Her hope?

“That we will identify and develop a new therapy for these cancers for those patients who don’t have many options,” Brooks says, explaining that patients often respond initially to a treatment, but after a year or two it can stop working and nothing seems to help.

She sees progress.

“For the lymphoma, breast and ovarian cancer target, we’ve developed a therapeutic that is a piece of DNA and we’re working with other researchers to get it into the cells better,” she says. “We have collaborations with Nathan Tumey and Anthony Di Pasqua [both assistant professors of pharmaceutical sciences at Binghamton] to try to improve the delivery, and we’ve applied for a Department of Defense grant to support the work. (“Yes, the Department of Defense supports cancer research!” Brooks says.)

On the pancreatic cancer side, she adds that they are trying to develop a drug versus going the DNA route, and she’s again working with Tumey to develop a drug for treating patients. “We have a lead structure and he’s making it better,” Brooks says.

But Brooks doesn’t spend all of her time in the lab. She’s also an award-winning teacher.

“I love explaining information in a way that clicks and makes sense,” she says. “I use analogies a lot that make sense to me and I love imparting not just knowledge but excitement over the material.”

She teaches first-year students the basics about DNA, RNA and proteins, but also about how drugs work on their targets and the different ways drugs can interact. “Basic science can be dry,” she says. “The other day I was explaining how drugs can bind and sometimes make a part of a protein get bigger and sometimes smaller. I was doing a clapping motion like the Baby Shark Dance and started singing the Baby Shark song in class.

“My mother used to do something foolish and silly and it helped me remember what she was helping me learn,” she adds. “Hopefully, Baby Shark will help students remember the actual thing we were learning.”

Brooks will teach about diabetes, starting with the actual disease state, to second-year students. “I’ll explain what’s wrong and how we can fix it with drugs. And I’ll teach endocrine and reproduction as well. In the spring I’ll teach a neuropharmacology course addressing things like psychiatry, seizures, ADHD, stimulants and pain.”

Third-year students will learn about hematology, immunology and oncology from Brooks, who is always looking to engage her students, whether in research or in the classroom. “One thing I love about being in a school of pharmacy is that teaching matters as well as research. I like the balance.”

Aside: Proteins are molecules in cells that are required for the structure, function and regulation of the body’s tissues and organs. Proteins are made up of chains of different types of amino acids, and each sequence determines the structure (shape) and function of that particular protein.