Professor discusses importance of ’the missing voices’

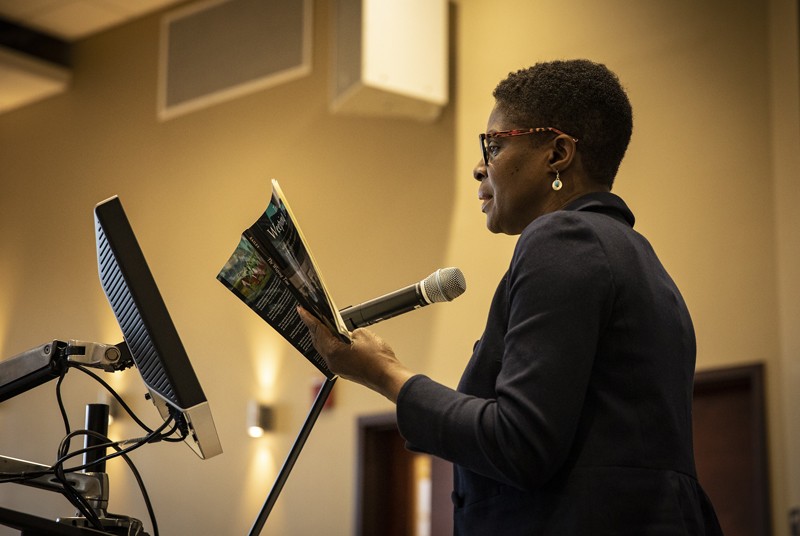

Anne Bailey delivers Harpur Dean's Distinguished Lecture

Incorporating the “missing voices” of the past can help higher education play a role in bridging the racial divides in contemporary America, Anne Bailey said at the Harpur Dean’s Distinguished Lecture on Feb. 21.

“Higher education is once again a battlefield,” she said. “The question of voice has never been more important.”

Bailey, a professor of history and Africana studies at Binghamton University, was chosen by Dean Elizabeth Chilton to deliver the spring-semester talk. She spoke for an hour on “The Weeping Time and Divided America” to a room full of students, faculty, staff and community members at the Innovative Technologies Complex’s Symposium Hall.

“I’m honored to be chosen because every year that I’m here – 14 years now – I get a better sense of the faculty,” she told her colleagues. “Our faculty is truly amazing. It’s humbling to think of the accomplishments of so many faculty here. It’s particularly terrific to be sharing with you today, understanding that many of you deserve to be (speaking).”

Bailey began the talk by reading from her 2017 book, “The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History.” The book describes the 1759 slave auction in Savannah, Ga., that saw 436 Butler Plantation Estates slaves sold. Starting the book with appeals and cries from those separated from loved ones not only gave Bailey and readers “the perspective of the enslaved,” but also laid the foundation to later examine the impact the breakups had on future generations.

“The overarching theme of my work is the question of voice – and the voices of African diaspora,” she said. “That’s why I started with the voices from the auction block. Those are voices we don’t normally hear.”

It took a decade for those voices to reach the front of the book, Bailey said, as some publishing companies wanted her to first introduce plantation owner Pierce Butler and his actress wife, Fanny Kemble.

“That’s the way we were told the story for generations,” Bailey said. “They are two significant people in their own right. But I wanted the slave voice not to be in the margin or the middle, but to be at the beginning. I’m glad that Cambridge University Press agreed with me.”

“The Weeping Time” is an example of how “missing voices” can offer fresh takes on well-known topics.

“The story that you know changes when somebody else’s perspective is taken into account,” Bailey said.

The same remembrance of history can be applied to higher education, Bailey said. The voices of African Americans, Native Americans and women have been subdued since the early history of higher education, she added.

“We owe much of our modernity to the innovation, research and imagination of faculty and students who have been part of higher education in the United States over all of these years,” Bailey said. “There’s no question about that. But we’ve also built a tradition on missing the voices of people of African descent, Native American and so forth.”

Higher education can be part of the solution, though, in areas such as curriculum content, physical space, representation and approach.

Bailey pointed to Yale University’s Calhoun College as an example of changing physical space. Established in 1931, Calhoun College was named for John Calhoun, a prominent lawmaker and ardent support of slavery. By 2016, Yale students were ready for change.

“Having Calhoun College so central to the university did not live up to some of Yale’s values today,” Bailey said. “They pressed the university to re-name the school.”

In 2017, the building was named in honor of Grace Murray Hopper, a 1930 Yale alumna who was also a pioneering computer scientist and a U.S. Navy rear admiral.

Bailey used a Binghamton University example to cite the missing voices in curriculum content. A student of Bailey’s named Erica Schumann examined 70 years of history courses at Binghamton and noted the gradual incorporation of missing voices.

“We see continued improvement,” Bailey said. “In 1947, it’s mostly the experiences of Europeans and global conquest. By 2017, the main U.S. courses are diverse – and race, class, sexuality and gender are reflected.”

Bailey said Schumann concluded that stories about African Americans, Native Americans and women must “remain in the forefront of our curriculum.”

“These groups are central to the formation and development of the United States in every time period and therefore should not relegated exclusively to special-interest history,” she said.

While Binghamton University advances its curriculum content, Bailey said she hopes more emphasis can be given to the history of the community, such as the abolition movement and the Native American experience.

“How can we find a way to acknowledge that we are a part of these traditions?” she asked. “How do we connect to that history and have people from those groups speak for themselves?”

Bailey brought the talk full-circle by playing a 1926 recording of “Kumbaya” by the Gullah Geechee Ring Shouters – descendants of the slaves who lived in the southeast Georgia region of the Butler Plantation Estates.

“As we figure out what’s going on in these troubled times, I hope we will all keep a sense of resilience,” she said. “These stories give me a sense of hope. Because of what (the slaves) went through, I know that whatever we are going through, this too shall pass.”