Ancient seawater may yield climate change insights

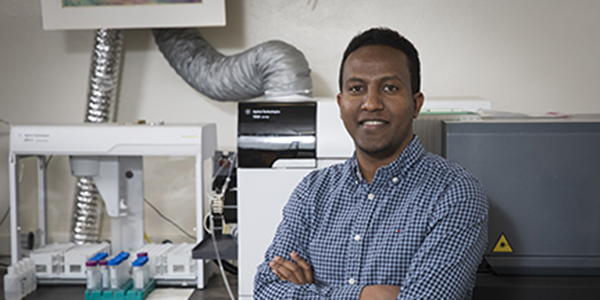

Binghamton graduate student Mebrahtu Weldeghebriel is a man of many firsts: He is the University’s first student from Eritrea, and he is presenting the first interpretation of what changed the chemistry of ancient seawater by analyzing minor and trace elements.

Scientists initially thought the chemical composition of seawater was constant. In the late 20th century, however, indirect evidence revealed that seawater chemistry has changed systematically at particular time periods during the past 550 million years. Knowing how the oceans and climate changed previously gives scientists insights into how it might change in the future.

Weldeghebriel aims to understand what caused these changes. He believes they could be a result of variations in the rate of seafloor spreading and fluctuations in hydrothermal vents, which release ions that react with the existing seawater.

To substantiate this idea, Weldeghebriel and his advisor, Tim Lowenstein, analyze marine halite, a mineral that traps and preserves seawater during its formation. They have collected more than 150 halite samples from different locations and time periods dating back as far as 550 million years.

To study the contents of these samples, they use a state-of-the-art Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer. First, a laser beam drills through a halite sample and evaporates the seawater inside (that’s the “laser ablation” part). The contents are then transported to a mass spectrometer, which analyzes the masses of individual elements and isotopes.

This allows for analysis of minor and trace elements in seawater in addition to the major elements. Minor elements comprise between 0.1 percent and 1 percent of a solution; trace elements make up less than 0.1 percent. Major elements comprise the rest.

Weldeghebriel’s research, which he presented at the Northeastern Section meeting of the Geological Society of America in 2018, is important because previous interpretations were based on analysis of major elements only. His new data has allowed him to narrow down other interpretations and bring forth hard evidence toward his interpretation.

While growing up in northeastern Africa, Weldeghebriel became infatuated with geology. He was still in high school when a group of geologists came to display minerals in the annual Eritrea Festival.

“When I saw these beautiful crystals and different colored rocks, it was in my mind,” he says.

At the Eritrea Institute of Technology, he graduated at the top of his class, winning a college gold medal. When Weldeghebriel reached out to Lowenstein about graduate studies, Lowenstein was impressed.

“He knew a lot about the subject material before he came here,” says Lowenstein, a distinguished professor of geological sciences. “I took him very seriously from the moment we emailed one another.”

After graduate school, Weldeghebriel is considering going into industry to work on Potash, minerals useful for agriculture. Later, he hopes to go on to become a professor. In Eritrea, Weldeghebriel says, there are limited resources because it is a developing country with economic inefficiencies and shortages. This limited him in his undergraduate research, as he only had the resources to do basic analyses.

“In America, there is a lot of opportunity,” he says. “I get one of the biggest opportunities coming here, because I can do whatever I want to do.”