Student-faculty collaboration moves Binghamton to next level of cancer research

Funding enables summer research experiences

Some research studies view cancer cells along a flat surface. However, the human body — where cancer-cell growth is more problematic than in the lab — isn’t flat.

Kush Grover, a third-year doctor of pharmacy student at Binghamton University, is part of a growing number of researchers examining cell configurations known as spheroids. They are three-dimensional, replicating how cancer spreads within a person. Although you can get some cool-looking shapes — Grover created one that looks almost like a poodle — the objective is more serious. Researchers want to see how medication fights these formations.

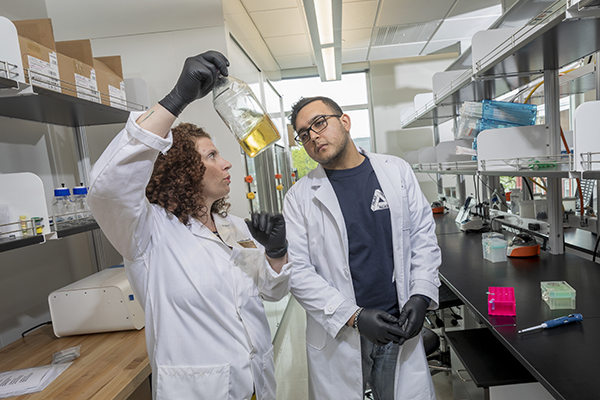

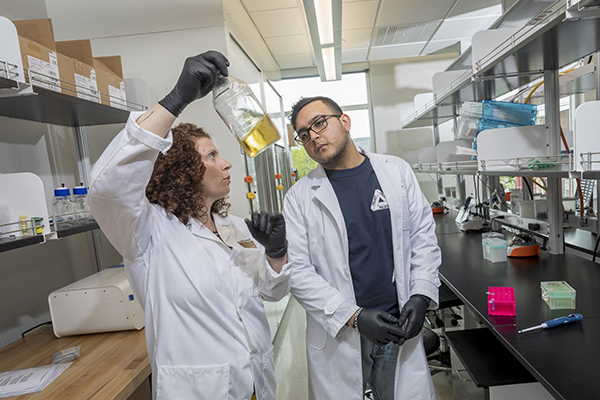

Grover began this research in summer 2018 with support from the Dr. Mildred Shellig Fund for Faculty-Student Research Collaboration, established a year earlier to provide School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences or Harpur College of Arts and Sciences students with a summer research stipend. Grover worked with Tracy Brooks, assistant professor of pharmaceutical sciences and Menner Family Endowed Faculty Fellow in the School of Pharmacy. Their collaboration continued in the 2018−19 academic year.

“My grandfather died because of pancreatic cancer,” Grover says. “I was intrigued by how it happened and what I can do about it as a researcher.”

Grover, of Seaford, N.Y., who earned his bachelor’s degree in pharmacology and toxicology at the University at Buffalo, first became fascinated by spheroids when he volunteered at an NYU-Langone Health lab. These spheroids will be the basis of his capstone project in the coming academic year.

Brooks says Grover’s research brought a new dimension to the pharmacy school and this pathbreaking work will help the school attract top students.

“Kush found that spheroids responded less to chemo[therapy],” Brooks says. “He formed these spheroids for five days, and another student asked, ‘What if we grew them for one, two or three months? Can they be grown that long? Do they respond to chemo?’” Brooks adds. “These questions have created new research for our students.”

Grover’s internship was made possible by a gift from Arnold Levine ’61, SD ’97, that established the Shellig Fund. In 1979, Levine and his colleagues discovered the p53 tumor suppressor protein, a molecule that inhibits tumor development. He was a full professor at Princeton University, then was microbiology chair at Stony Brook University before returning to Princeton to chair molecular biology. From 1998 to 2002, he was president at The Rockefeller University in New York. Currently, he’s a professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J.

“I’m an elder statesman in the field and I want to pay back,” Levine says. “Giving to one’s alma mater is the most important gift you can make. Binghamton’s professional schools are producing work that will be meaningful to future populations.

“One of the wonderful things about education is that you never know who is going to catch fire and make an important contribution,” he says. “I hope I can help make that happen for someone I may never meet.”