Island solitude is key for art professor’s latest project

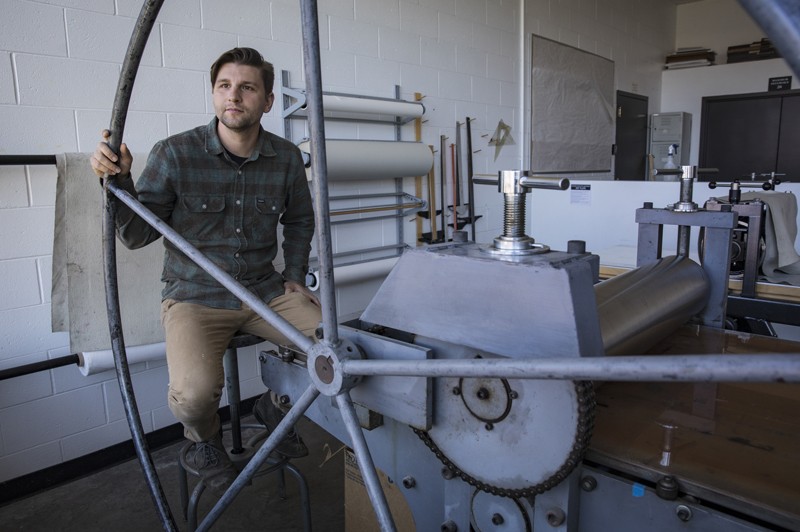

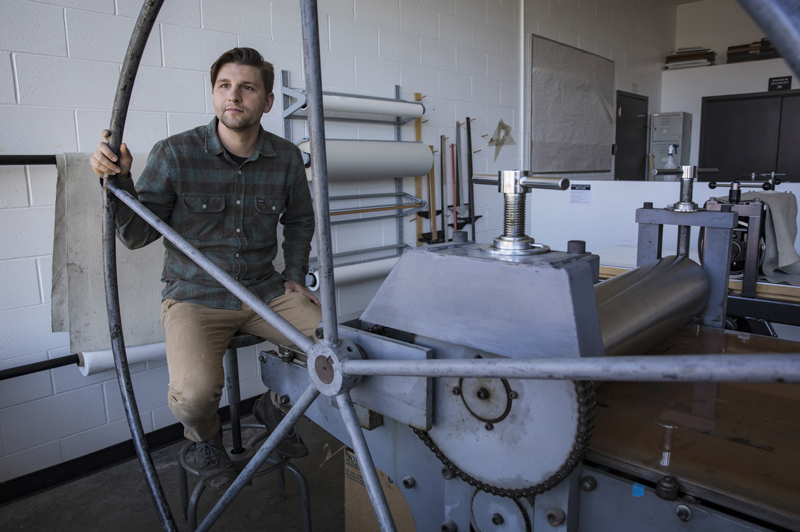

Colin Lyons spent part of summer living and working on remote Lake Superior site

Colin Lyons knew that a summer residency program on a remote island in Lake Superior would force him to miss the first day of the fall semester at Binghamton University.

So the assistant professor in the Department of Art and Design made the most of his newfound environment: He produced a video lecture from the Rabbit Island shore for his students.

“When the other Rabbit Island residents were dropped off, I left a flash drive with the (program) director on the boat,” Lyons said. “He took it back to the mainland and mailed it to Binghamton. It felt appropriate because I’m teaching a site-specific installation (class). It allowed students to think about what it means to make things on site. That’s the push and pull between this world and island life.”

Lyons was one of only three applicants to be awarded residencies for the 2019 Rabbit Island Program. The residencies allow artists to live and work — mostly alone — on the 91-acre island for two to four weeks, as they investigate and challenge creative practices in an uninhabited, wilderness setting.

The Ontario-born Lyons spent much of August on the island starting a project called “The Laboratory of Everlasting Solutions.” In this printmaking-based installation, Lyons is adopting the role of a practical alchemist who is exploring the field of geoengineering and its technologies and histories.

“The project would consider the intersection between alchemical philosophies and contemporary climate-engineering, resulting in a laboratory that imagines fictitious and highly impractical prototypes,” Lyons said in his project description. “The laboratory will present a future-oriented satire: time capsules that project a vision of the near future based on the realities and anxieties of the present.”

Rabbit Island, located a little more than four miles east of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, was the ideal spot for Lyons to kick off the project.

“I wanted to go to a place like Rabbit Island where I could begin the process of getting into character — getting into the mind-space of an alchemist,” he said. “I needed an isolated space for some of the research.”

The arrival

Lyons drove to Houghton, Mich., where he was then transported to Rabbit Bay and a boat that took him to Rabbit Island for an overnight orientation.

“You learn how to use the island responsibly, because not every artist is going to come in with a lot of experience in the wild,” he said.

While obviously remote (the rabbits were hunted and killed long ago by the mainlanders), the island setup was a pleasant surprise to Lyons. Shelter came in the form of a three-sided cabin with a kitchen and bed, and a small studio with a sauna in the back. There was a water filtration system, but no plumbing.

“For the bathroom, it was basically a wooden box that you threw leaves on top of,” he said. “There’s an idea of ‘leave no trace’ on the island. Don’t do anything that will have a long-term impact on the island.”

Lyons brought a small amount of food on the trip and caught five fish during his stay. He mostly “feasted” on the island’s abundance of wild raspberries.

“Whenever I did an exploratory hike around the island, I stopped and ate raspberries for an hour!” he said.

Hikes would take two hours to go all the way around the island, said Lyons, who added that it was easy to get lost and disoriented if he tried an inner route.

“It’s hard to go in-land,” he said. “It’s dense. I’m Canadian, so I’m used to being in the forests and wild places that aren’t manicured. But the density of this underbrush was amazing.”

For emergency purposes, Lyons had access to a radio with direct lines to Rabbit Bay and the U.S. Coast Guard. One of the biggest surprises was discovering that the island had cell service.

“It’s strange to be on an island, but fully connected,” he said. “I wasn’t expecting that: I told people I’d be off-grid and not to call me. It was interesting to be isolated, but know that I could be connected.”

Lyons was able to talk with his family, which includes wife Andrea Kastner, a lecturer in the Department of Art and Design. Otherwise, he was solitary — with the exception of a researcher who spent several days studying the island’s vole population and the arrival (at the end of his residency) of two poets who planned to verse about the island’s bugs.

The research

Lyons spent much of his time reading alchemical books and dictionaries that he brought from home and the library. It was important, he said, to try to understand the logic behind the imagery and illustrations.

“I don’t think I could’ve done this anywhere else,” he admitted. “When do you have time to read a dictionary? It’s weird (content). How can you get in the right mind-space to suspend disbelief?”

Lyons, who joined the Binghamton University faculty in 2017, also started work on one of the prototypes of The Laboratory of Everlasting Solutions: an illuminated manuscript of a 1970s congressional document on weather modification and climate engineering. His goal is to transcribe the 746-page document on paper using sulfuric acid as the pigment.

The texts produced by the acids are initially nearly invisible, but they will reveal themselves over the next couple of decades as the acids discolor and the paper is destroyed.

“I see that as a parallel to the start window we are working with now for doing something about the climate-change crisis,” Lyons said.

Lyons was able to transcribe 40 pages of the document. He discovered an even more isolated location within the quiet to conduct the work: a tree perch built by a previous resident artist.

“It was a wooden platform 20 feet off the ground,” he said. “It was a great place to do research and all of my transcriptions. If there was anywhere I could feel that isolation, it was up in that canopy.”

The reflections

Another highlight of the residency for Lyons was watching “spectacular” summer storms approach the island.

“On an island, you can see them coming forever,” he said. “I’d know from the radio when the storms were coming in, but there’s something about being unprotected there. You always feel the elements.”

Lyons also learned a lesson about the concept of island time.

“I thought days would be slow and drag on,” he said. “Instead, I would get to the end of the day and say: ‘Wow! The sun is setting. I didn’t see that coming.’ There was an element of noticing different things: the sound of the rocks on the coast. You’re unaware of time passing and more aware of the sounds and forces happening there.”

While Lyons also worked to make crystallized chemicals for stalagmites and test experimental pyrite batteries (more prototypes for The Laboratory of Everlasting Solutions), he admitted that one of his residency goals was not to make too much. His exhibitions have been featured in locations ranging from Rochester and Cleveland to Vancouver and Yukon.

“It’s not the most conducive place to physically create,” he said of Rabbit Island. “It’s about working through ideas. I’m looking at this as a multi-year project. It was beneficial for me to get the research and thinking under me rather than making objects that I can take back.”

For Lyons, the cast-away Rabbit Island experience was professionally rewarding for a project in its infancy.

“Geoengineering is about simulating a natural ecosystem,” he said. “These strategies form a dystopian contingency plan that, employed alongside mitigation efforts, strives to preserve a close approximation of our present environment. But what is a natural ecosystem even like? We are so far removed from it here. I wanted to empathize with it and be more in touch with that reality.”