Decker alumna helps keep world healthier

Annette Bongiovanni '80 has had an (extra) ordinary career

Even amid the disco-era fashions on Binghamton University’s campus in the late 1970s, Annette Bongiovanni cut a striking figure.

She attended the School of Nursing wearing green plastic galoshes and a full-length black cape. Her natural curls were permed for added emphasis, and she often wore Tiki-inspired jewelry.

While some professors overlooked her quirky nature, others qualified their praise with, “She’s a good student, but she’s a little weird.” Few predicted the storied path ahead of her — and that includes Bongiovanni herself.

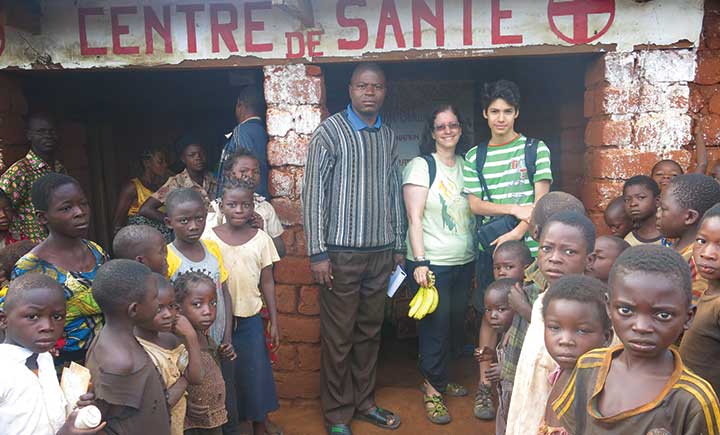

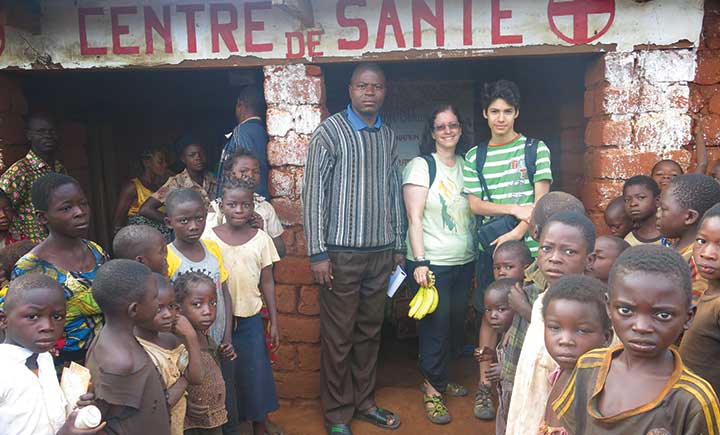

In the four decades since leaving Binghamton, Bongiovanni ’80 has traveled the world for her career in public health policy, evaluation and research.

She has worked for the United States Agency for International Development, World Bank and World Health Organization and collaborated with the National Institutes for Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and a who’s who of top-level foundations and universities, designing and leading initiatives to enhance maternal, neonatal and child health; improve reproductive health and family planning; and curb the spread of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases.

Bongiovanni originally thought about being a cardiac surgeon at age 16, when she read about Norman Shumway’s first heart transplant. She entered nursing school, though, wanting to become a social worker and thinking she could earn money for a master’s degree by working as a nurse for a few years.

As an undergrad, Bongiovanni focused on community mental health: “I ended up loving nursing. By the time I graduated, I never doubted that I wanted to be a nurse.”

After Binghamton, she became a nurse at Stanford University, treating some of the first HIV patients in California’s Bay Area. Later, she was a critical-care nurse working with heart and heart-lung transplant patients — and with Shumway.

As a hobby, Bongiovanni made porcelain masks, so in the mid-1980s, she cashed out some of her retirement savings and apprenticed with a traditional mask carver in Bali for a couple of months. She fell in love with Indonesia and returned to become a project director for Project HOPE in the pediatric and neonatal ICU at the University of Indonesia’s teaching hospital in Jakarta.

The job was literally and culturally a world away from Stanford. “There were rats falling from the ceiling onto the babies’ isolettes,” she says. “There were feral cats all over the ICU. I remarked on how many cats there were, and they were so proud that I had paid them a compliment — the more cats that you had, the fewer rats you had!”

Bongiovanni advised Indonesia’s Ministry of Health about creating a policy requiring the certification of pediatric intensive-care nurses, resulting in a program that continues 30 years later. It didn’t seem like a big deal — she was just using common sense. An international consultant saw her potential, though, and suggested a master’s in public policy from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

After grad school, Bongiovanni worked as a consultant for a variety of universities and nongovernmental organizations, but she also did per-diem shifts at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and later at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

A LIFE LESS ORDINARY

Bongiovanni has had what she considers an “average” career in the global-health sector, but it’s taken her to nearly 50 countries — from Armenia to Ghana and Ukraine to Congo — and she’s published more than 30 research papers and a few peer-reviewed publications. She wrote policy briefs for then President Bill Clinton, then First Lady Hillary Clinton and Congress, and she led an initiative for the U.S. Agency for International Development Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean that brought together 13 ministries of health to ratify a common strategy to reduce maternal mortality. The program was supported by the first ladies of the Americas.

Currently the vice president of technical services for the Virginia-based International Business and Technical Consultants Inc., Bongiovanni leads a global team with staff in the United States and abroad who are researching the effectiveness of U.S. foreign assistance, such as aid programs to fight the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Throughout her 40-year career, she has retained her love for the Decker School, crediting not just the practical nursing knowledge she gained at Binghamton but also the lessons about empathy, inspiring trust in patients and working as part of a team.

“The Decker School taught me a lot about the patient as an individual,” she says. “They come from different walks of life, but they’re all treated equally. To me, that’s the most beautiful thing about being a nurse — everyone is treated the same in a patient gown, and no one person is more important than another. Everybody gets out of bed one foot at a time.”