Provost’s book examines how race has shaped the Constitution

'Promises to Keep' places the African-American experience at center of U.S. history

Idealistic students and Black Lives Matter activists have Donald Nieman feeling optimistic about the country’s long-standing battle for racial equality.

“There are people who won’t let us forget that this is not a society in which all live equally and equitably,” the Binghamton University executive vice president for academic affairs and provost said. “They will not let us become complacent. They will stick a finger in our eye. That’s what gives me optimism.”

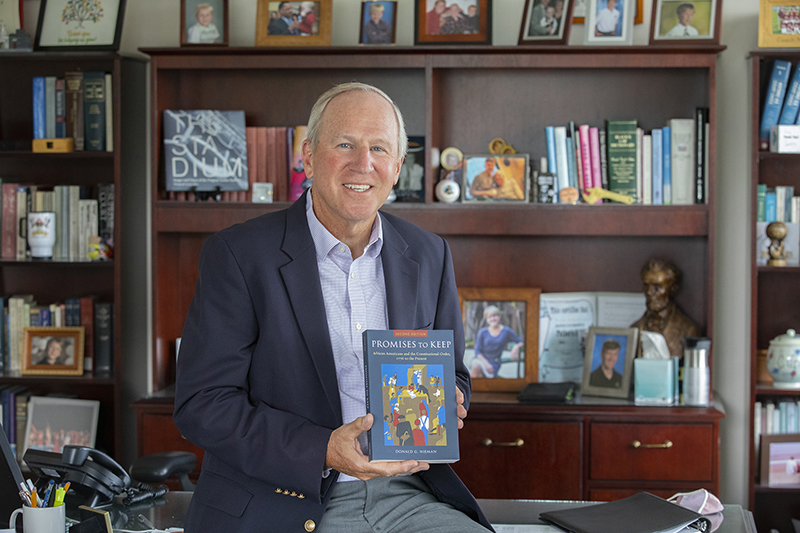

In a tumultuous year that has seen the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police and protests and marches across the country, Nieman brings a historical perspective to today’s racial issues with an updated edition of his 1991 book, Promises to Keep: African Americans and the Constitutional Order, 1776 to the Present.

The second edition, released in the spring by Oxford University Press, examines the history of the Constitution and U.S. laws through the African-American lens and experience. The book — written in a way that makes its content accessible and appealing to a mainstream audience — takes readers on a journey from Revolutionary-era race debates and Reconstruction after the Civil War to the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century and modern topics such as police brutality and voter suppression.

“This is what my scholarship has focused on — issues of law and race in U.S. history,” Nieman said. “It has occupied my scholarship since I was in graduate school. It grew out of coming of age during the time of the civil rights movement and being struck and moved by issues of race and the use of protest, civil disobedience, and the political and legal processes to advance the cause of racial equality.”

Nieman said the original version of Promises to Keep was well-received and incorporated into several of the classes he taught, as well as classes at many universities across the country. He particularly recalled a review from the time that praised the book as being the first Afro-centric history of the U.S. Constitution.

“African-American history is American history,” he said. “You can’t separate them.”

But the hopes of doing a second edition stuck with Nieman as the 21st century proceeded.

“For the past 20 years, I’ve been either a dean or a provost,” he said. “I’m a dad and the husband of a professional woman. I never thought I would have the sustained time to devote to (an update).”

The 2014 racial unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, along with the election of President Trump and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, provided the motivation to revise the existing chapters and add a new chapter to discover “what has happened since 1990.”

“I’m under no illusion that the world needs this book,” he said. “I needed to write it. Hopefully, people will find it useful.”

The latest chapter (“The Color-Blind Challenge to Civil Rights”) examines the affirmative-action debate, mass incarceration, the War on Drugs and police violence against African Americans.

“Color-blind Constitutionalism” is at the heart of the book, Nieman said, as “the argument emerged at the moment that Jim Crow segregation was being broken down in the 1960s.” Many conservative Supreme Court justices over the past half-century have argued that the Constitution is color-blind and that race cannot be taken into account when developing remedies to the effects of past discrimination.

“That would be fine if we lived in a society that approached anything like being color-blind,” Nieman said. “But we don’t. In order to root out the legacy of discrimination, you need color-conscious remedies like affirmative action and drawing electoral districts in ways that will allow African Americans to elect candidates of their choice.

“There’s been a dueling argument in the Supreme Court since the 1980s over the appropriateness of color-conscious remedies. I’m sad to say that the defenders of color-conscious remedies — William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, John Paul Stevens, Harry Blackmun — have lost. But Ruth Bader Ginsberg remains a persuasive voice for the fact that we don’t live in a color-blind society.”

Another key element of the book is highlighting those “outside the system” who apply the pressure that can produce change.

“That’s true whether it’s abolitionists in the early 19th century, radical Republicans in Reconstruction, the NAACP in the early 20th century or the March on Washington movement,” Nieman said. “There are people who force us to come face to face with unpleasant realities.”

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was one such person, Nieman said, who worked outside the system to engage in civil disobedience and call attention to the fact that racism is systematic.

“It wasn’t just disenfranchisement laws and Jim Crow,” Nieman said. “It was an economic system that relegated African Americans to an inferior position and subjected them to worse health, worse educational outcomes and living in communities where interactions with police would be fatal. King knew all of these things had to be challenged.”

In Promises to Keep, Nieman also lays the groundwork for the reader to gain additional knowledge on various topics and events from the book. A 17-page bibliography offers hundreds of books and sources — particularly from the past 70 years — that delve deeper into each chapter.

“If you want to read about busing in (1970s) Boston — a pivotal moment — here are five books on the subject,” he said. “It was controversial at the time, but the perspectives have since evolved. While Anthony Lukas’ Common Ground is a great read, it’s a read that’s grounded in the (views) of ethnic whites. Getting different perspectives is important.”

Nieman hopes readers finish Promises to Keep with an understanding that “racism is deeply woven into the fabric of American life.”

“It’s not something we escaped when we passed The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965,” he said. “We did not overcome in the civil rights movement. But if we recognize the reality and try to come to terms with it, that’s the only way we are going to root out the systemic injustice that exists in our society.”