A look back at social activism at Binghamton University

Fifty years ago, on July 1, 1971, Congress ratified the 26th Amendment, granting the right to vote to U.S. citizens aged 18 and older on the heels of a decade that saw unprecedented levels of activism among young adults in America, including at Binghamton University.

Dissent on campus

Binghamton’s campus was alive in the early 1960s with students protesting the Civil Defense drill, which required all citizens to go to a designated fallout shelter in preparation for potential nuclear bomb attacks during the Cold War with Russia. Students also staged protests over campus social regulations, such as a requirement to dress up for dinner (so many students showed up to dinner in Bermuda shorts one night that they couldn’t all be kept out and the rule was discarded going forward).

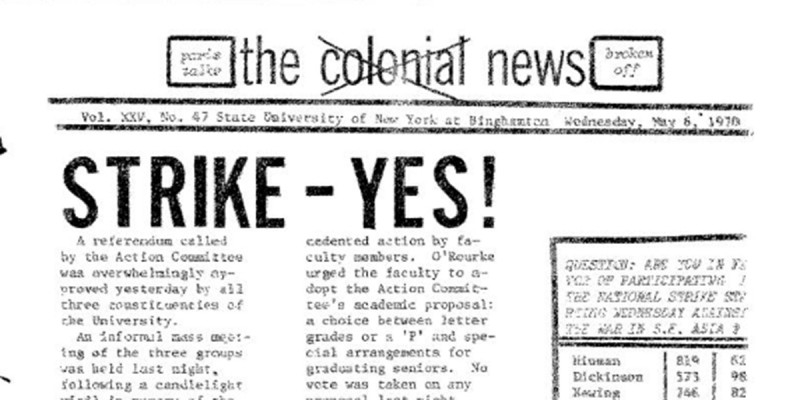

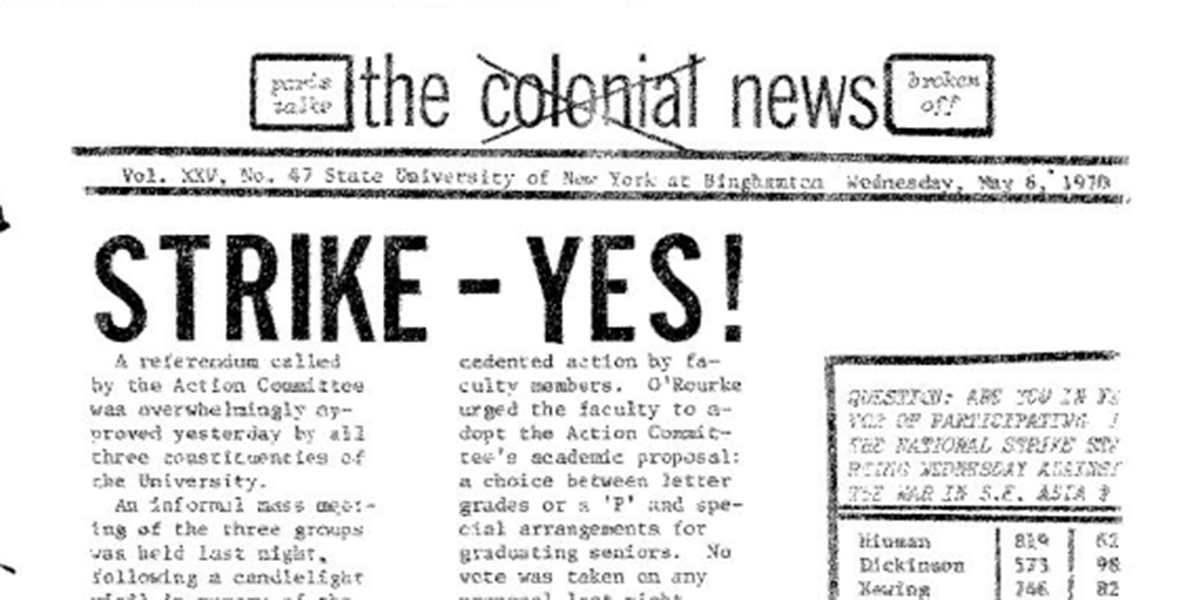

By the mid-1960s, students’ attention turned to issues like the Vietnam War and civil rights. Binghamton’s first teach-in on the Vietnam War was held in 1965, and countless marches, protests and vigils followed. In May 1970, the antiwar movement came to a head as the entire campus went on strike and classes were canceled for the remainder of the semester following the deaths of four students at Kent State University. Faculty voted overwhelmingly in favor of the strike and “free university” was instituted, essentially a series of seminars about topics related to the war.

Shortly after the strike began, then-Binghamton University President Bruce Dearing led a march of thousands of students and community members from campus to the courthouse in Binghamton to protest the war. According to an article in the May 12, 1970, issue of The Colonial News, the student newspaper on campus at the time, 7,500 people participated in the eight-mile march, the “largest anti-anything demonstration in Broome County’s history.”

Student anti-war sentiment was immortalized shortly afterward, when, beginning with the May 5, 1970, issue, “Colonial” was crossed out in the paper’s masthead to protest perceived American colonialism in Southeast Asia. The paper was renamed Pipe Dream the following fall.

The Colonial News editorials sometimes showed opposing perspectives on the country’s anti-war movement. The May 15 issue printed a letter from the Black Student Union about the Augusta, Ga., Riot of May 11–13, 1970, when four Black men were shot in the back by members of the National Guard while protesting the suspicious beating death of 16-year-old Charles Oatman in a county jail. The letter pointed out that “Blacks in Augusta, Georgia, as well as Blacks across the nation have been sustaining the oppression, ignorance and belligerence of racist whites, guardsmen and police for six days, or for that matter, three hundred years,” but the only thing getting the attention of the “very aware whites” on campus was the relatively isolated incident at Kent State University.

Binghamton University was predominantly white at the time. Islah Umar ‘73 (who legally changed her name from Margie Glenn in adulthood) was one of the very few Black students on campus. She described her experience as a person of color at Binghamton as being “a speck of dust in a sea of white.”

She first came to campus for the Transitional Year Program (TYP) — the original name for the present-day Educational Opportunity Program — summer session in 1969. Her recollection of her first experience with the full campus community set the stage for a college career full of various kinds of unrest.

“In September,” she said, “I was rudely awakened by the fraternities that took over the Student Union. I was scared because they were all standing on tables and they were yelling at people…recruiting people for the fraternities. I didn’t expect it. There were a lot of really big men with beards, and it looked like an insurrection.”

Umar’s first protest came the following spring, when she and other students of color occupied the administration building on campus for several hours, demanding more representation on campus.

“Eventually, the president came out and asked us what our demands were,” she said. “We had a spokesperson or two and they told him we want more ethnic staff — staff of Black and Puerto Rican descent. We want more courses that are relevant to our experience. And in September of 1970, we got everything we asked for.”

Umar recalled having the support of faculty and TYP staff and the following fall, the Black Student Union was given a large budget for hosting cultural programming on campus. Performances included famous Black artists like Roberta Flack, Freddie Hubbard, Duke Ellington and Miles Davis. Umar worked for the campus radio station, so she got to interview many of them.

A number of influential Black voices joined the faculty as well, including Floyd McKissick, author of ⅗ of a Man, and Loften Mitchell, a playwright and theater historian. Umar’s most impactful professor was Percival Borde, associate professor of theater arts and Black studies.

“I did a play on the Vietnam War,” Umar said. “I’m a New Yorker, I’m a theater person, so I told the story the way it was. I don’t think I was wise enough to temper my statements. I talked about the president at the time. I talked about the hypocrisy — the reality that African Americans were pushed to the front of the war and killed, just mowed down, and how other races were able to be commissioned as officers and they never saw combat. I did it twice, and people didn’t like what I did too much, but I felt like I had to tell the truth.”

The youth vote

With so many social issues at the forefront of student consciousness, it is little surprise that many pushed for youth suffrage. After all, 18-year-olds were old enough to be drafted into a war that many of them opposed, so why shouldn’t they be old enough to vote? Up until the ratification of the 26th Amendment, each state set its own voting age — most at 21 years old. In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed an extension of the Voting Rights Act that lowered the voting age to 18, but it was challenged in the courts. The Supreme Court ruled that the lowered age only applied to federal elections. In response to thar ruling and student protests across the country, the 26th Amendment was introduced into Congress to lower the voting age across the country to 18.

Since its ratification, the 26th Amendment has been used to challenge voting laws that impact students, such as voter ID laws and polling places that are not accessible to students. One concern that cropped up prior to the 1972 presidential election was that the student vote could overwhelm small community governments if students voted in local elections where they went to college. Many communities, including Binghamton, actively tried to prevent students from voting locally, saying they should vote in the district their parents lived in.

An article in the Jan. 8, 1971 issue of the Pipe Dream, titled “The 18 year old vote; where students fit in,” claimed students were being denied the right to register to vote locally by the election board. A spokesperson for the board stated that students who were claimed as dependents by their parents for tax purposes were “legal residents” of the county their parents lived in and must register there.

The election board argued that in a small community like Vestal, a heavy student voter turnout could greatly influence local government results and claimed that students weren’t really affected by local politics. The Pipe Dream article argued that nearly 2,000 students lived in the community for nine months of the year, paying rent and utilities and often holding down jobs. In addition, it was difficult for students to stay engaged with issues and candidates back in their hometown.

Finally, the article argued, over 3,000 students were counted in the census based on where they lived while at school, and the local community received state aid based on those numbers. It wasn’t fair that the community could count those students as residents when it served their purposes but exclude them at other times.

In 1979, in Symm v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that college students have the right to register to vote where they are attending school, using the 26th Amendment to argue that election officials cannot place additional burdens on college students to provide residency than they do on other voters.

Fortunately, Binghamton University has enjoyed a great relationship with the Broome County Board of Elections (BOE) in recent years. The BOE works closely with the Center for Civic Engagement (CCE), the office that coordinates voter engagement on campus, to ensure that students have every opportunity to register locally if they choose to. The University, which encompasses three of Vestal’s 19 election districts, hosts an on-campus polling site for residential students, thought to have originated in the later 1970s.

Since the CCE began tracking Binghamton University student voting rates in 2012, the percentage of students registering to vote and voter turnout at the on-campus polling place have steadily increased, in part due to CCE efforts to streamline the voter registration process, while reflecting a broader increase in youth voting rates nationally as students respond to civil rights issues that are still in the headlines today.

The murders of Black individuals like Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and countless others by police officers present startling parallels to the injustices Umar and her peers fought against in the 1960s and ’70s. Students continue to be active today in the fight for racial justice and other causes, both on and off campus. As far as the United States has come on many social issues, there is undoubtedly still work to be done, and today’s Binghamton University students are still contributing to the call for change echoed by youth across the country.