Hit the streets: Mass Mobilization Project tracks protests around the world

If you’ve noticed an increase in protest movements around the world recently, you’re not alone. David Clark, professor of political science and associate dean for undergraduate studies in Harpur College, has noticed it too — and he has the data to back it up.

“There has been a broad trend over the last five or six years toward protests that are demanding the removal of governments,” says Clark. “Four of the biggest years in our data have happened since 2015.”

The data Clark is referring to is part of the Mass Mobilization (MM) Project, a massive database that tracks events in 162 countries where citizens have publicly protested against the government. With data covering more than 15,000 events since 1990, information on protestor demands and government responses is also cataloged.

The project is sponsored by the Political Instability Task Force, a research group funded by the CIA interested in what causes state failures. Clark began working on the MM Project in 2013.

“We wanted to understand a few basic questions about what leads citizens to mobilize against the government and what the government does back to them,” says Clark. “There was very little data on this at the time, so we had a pretty ambitious scope.”

While he’s always had an interest in political science, Clark says his real passion is solving puzzles, making him particularly suited for a project of this size.

“Politics presents a lot of puzzles,” he says. “It’s that puzzle and problem-solving orientation that is particularly appealing to me.”

With the help of graduate students, the researchers began uncovering events that involved 50 or more public protesters. Smaller events — for example, a handful of people protesting on a street corner — are numerous and unlikely to attract significant government attention, they determined.

As more data were compiled, Clark began discovering trends and patterns. One finding is that protests that adhered to an organizational structure, even if an informal one, tended to be more effective and less violent than unorganized protests. Clark identified three reasons why:

- Organized movements tend to have more focused goals, demands and methods, and are often able to rein in or eject violent members.

- Government forces have a more difficult time justifying violent responses to protesters who are less violent themselves.

- Governments are less likely to respond violently when organized protesters are able to broadcast their story more effectively to the public.

Tracking these incidents can affect researchers’ mental health, Clark acknowledges. Protestors typically face difficult and sometimes tragic circumstances, and reading hundreds of articles on the topic takes its toll. However, Clark says he finds himself moved by many of the stories.

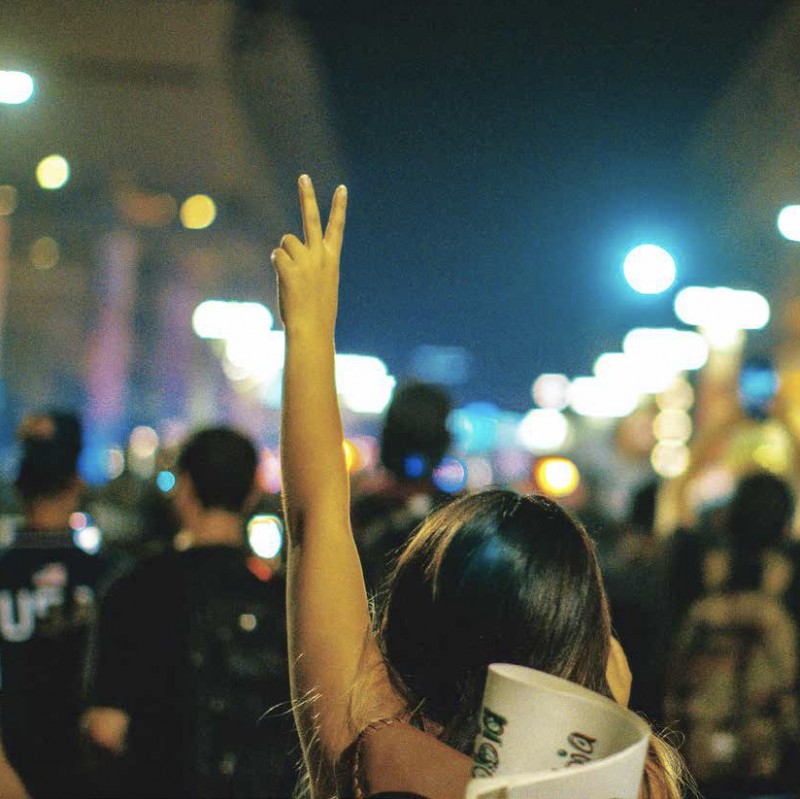

“Protesters are often taking incredible risks, and it is inspiring that people are still willing to get out and demand that they be able to live their lives in some kind of safety,” he says.

While the MM Project doesn’t account for events in the United States, Clark says it’s important that Americans understand the ramifications of the findings.

“There have been broad trends over the past decade toward populist governments and movements, and they are becoming more successful in winning office across the globe,” he says. “Understanding protests in this contemporary setting is important for understanding where we are and what it means for American democracy.”

Citing the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol as an example, Clark says, “It may certainty seem like an outlier event when you look at the sweep of American history, but in terms of what we’re seeing around the world, it is not really much of an outlier at all. It fits a pattern.”