Briloff Lecture speaker Liz Nesvold ’90: ethical decision-making is not always black and white

Wall Street banker discusses accountability in investment banking

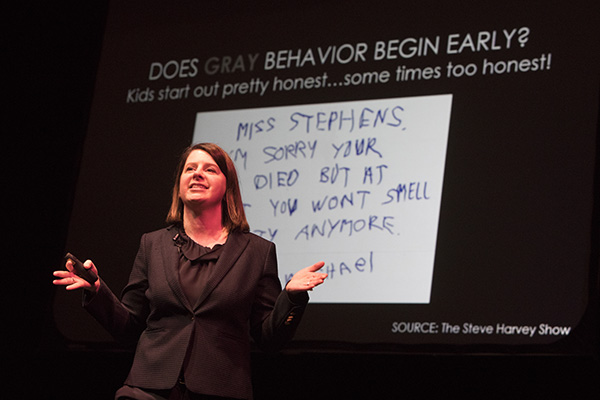

“When do good people go bad?” asked Elizabeth “Liz” Nesvold ’90, co-founder and managing partner of Silver Lane Advisors, who was the keynote speaker for the 29th Abraham J. Briloff Lecture Series on Accountability and Society.

“This is the talk that almost wasn’t. I speak all over the country, but never on ethics. Then it dawned on me — who better to talk about ethical decision-making than a Wall Street investment banker?” joked Nesvold, who earned a bachelor’s in political science with a minor in economics from Harpur College, and an MBA from Fordham University.

Nesvold — who has overseen more than 150 strategic capital investments during her career — said in her March 1 talk that perfectionism pervades the financial industry. She said this kind of workplace culture influences people to hide their mistakes, which can lead to more widespread corporate corruption.

“Wall Street does not tolerate failure, but we have to make it OK for people to admit when they’ve made mistakes,” she said.

Nesvold said more damage is often done to the credibility and integrity of an organization from the actions taken after a misstep than from original mistake itself.

“It’s easy to hide things in financial services, especially when you’re dealing with large amounts of money. But if you have one of those awful moments and feel in your gut that something’s not right, trust that feeling,” she said. “I believe most employees who bend or break ethical rules do so because they’re afraid to trust their instincts and speak up about a mistake.”

Informing decisions based on past mistakes is also crucial to creating stronger organizations, she said.

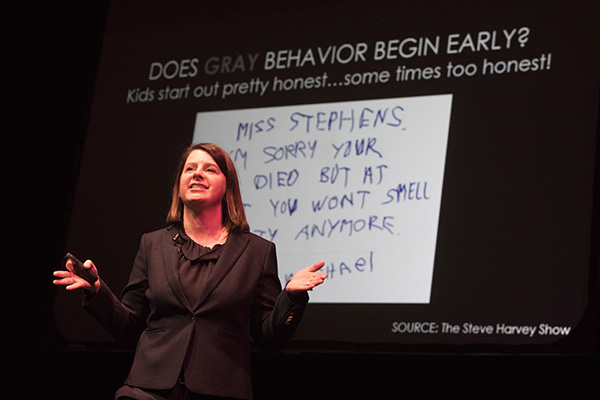

“Sometimes good comes out of failure. Failure is not terminal — it’s an opportunity to pivot, take ownership and create better processes,” she said. “The serious issues arise when the gray areas continue to darken.”

Bad behavior exists on a spectrum, she added, noting that in her tenure as a leader, she’s seen questionable employee actions that have “ranged from gray to black.”

She also said good managers should put effort into improving ethicality among their employees, including through use of compliance technology to monitor online activity on corporate devices and track bad behavior.

“We hired an incredibly likeable analyst who was a great team player. Soon into the job we saw that she was not getting her work done and we couldn’t figure out why. Turns out, she had logged into Facebook more than 900 times during work hours over a two-month period,” she said.

Nesvold said there was a vice president at her firm who also wasn’t meeting performance goals, but she suspected it wasn’t because of social media.

“We were able to detect that he was logging into another company’s network to advise on outside investment deals. I told him this was inappropriate behavior and he couldn’t understand why. The ethical implications of his actions didn’t resonate until I explained that I should be getting compensated for his side deal since he was technically working on my time,” she said.

Nathan Oliver, a junior majoring in business administration, asked, “At what point does promoting a lesson-learned culture result in organizational carelessness?”

Managers should reward their employees for making quality decisions, Nesvold explained, and not just for the results of their behaviors.

“As leaders we have to acknowledge that everyone makes mistakes. It’s generally not the first detectable error that hurts a company, it’s the compounding errors and cover-ups that cause the biggest problems,” she said.

“We are continually reminded of the importance of this topic as well as teaching ethics in business school through public issues of well-known individuals and iconic firms,” said School of Management Dean Upinder Dhillon on the significance of the Briloff Lecture series.

Nesvold concluded that she is optimistic about shifting the Wall Street mindset when it comes to ethical failures.

“Some say the mistake of one person contributes to the failure of many,” Nesvold said. “I say the morality of one person contributes to the success of many.”