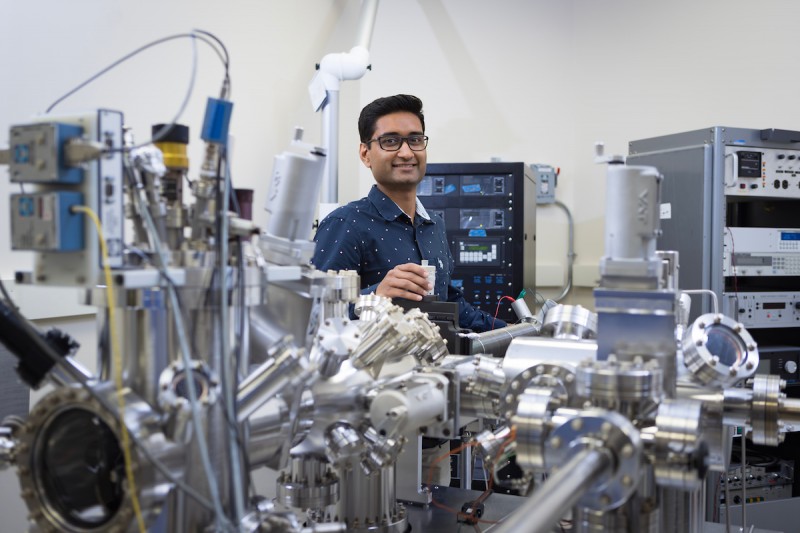

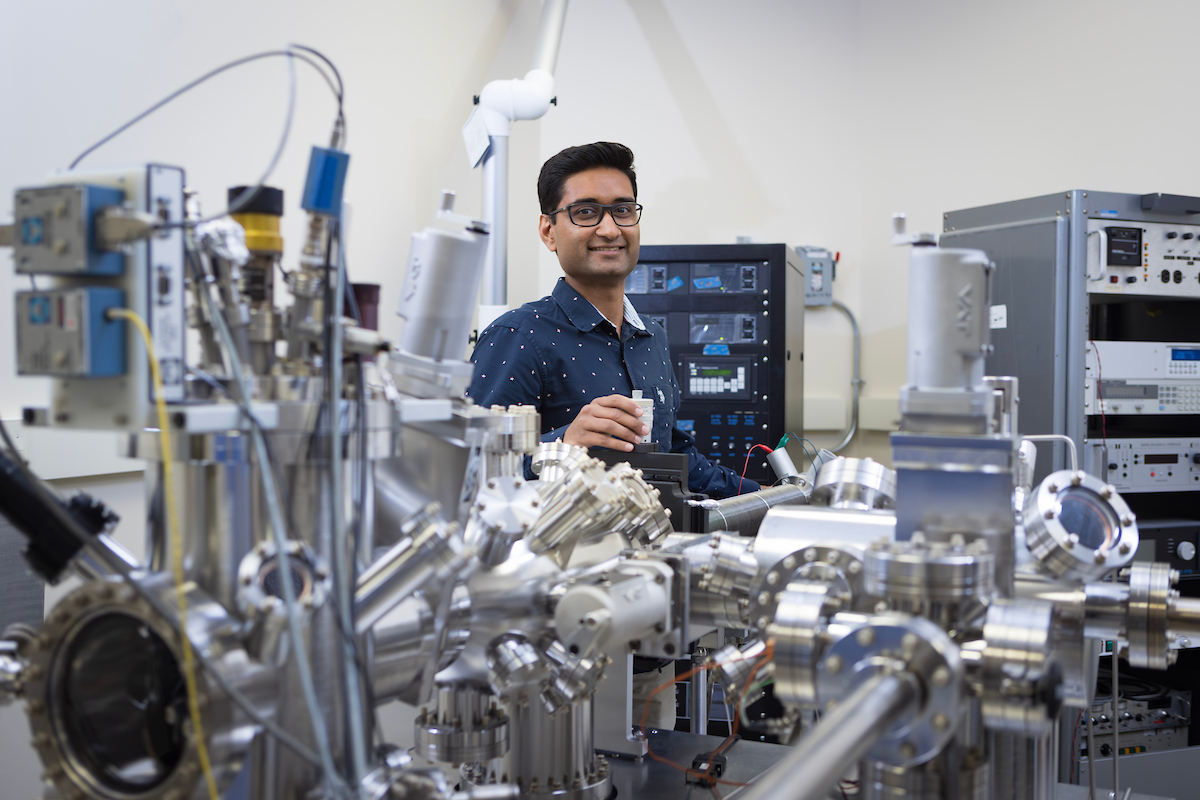

Doctoral student finds calling in materials research

Shyam Patel conducts research at both Binghamton and Brookhaven National Lab

Before Shyam Patel came to Binghamton to pursue a doctorate in materials science, he studied physics and nanotechnology at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia. It was there that he grew fascinated with the instruments used to view the world at the atomic scale, enchanted by towering microscopes that resembled steely spaceships.

His hunger to learn more about working these “spaceships” drew him to Binghamton University. He now studies how metals and their atoms move and dance under different environmental conditions. Understanding the mechanisms of these phenomena — such as corrosion or catalysis — can lead to the design of next-generation materials that could power the smallest computer chips or the hottest jet engines.

“For me, the main driving point was to separate myself from the rest. In my view, the way of doing that would be to not only have book knowledge, but also have hands-on experience with these instruments and be able to independently run them — which I do right now,” Patel said. “I saw that this was a possibility under Professor [Guangwen] Zhou at Binghamton.”

Patel is now in the final year of his studies at Binghamton, as a member of SUNY Distinguished Professor Guangwen Zhou’s Surface and Interface Science Laboratory. He is also a visiting PhD researcher at the Brookhaven National Laboratory, a longtime partner of Zhou’s lab.

In this time, he’s helped author multiple publications in leading journals, including Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He has also become the first Binghamton student to place as a finalist for the Wayne B. Nottingham Prize, an award given to student researchers in the field of surface science.

“The beauty in the stuff that we do is we look at the surface of materials at high temperatures. A lot of the time, we’re looking at surfaces at 800°C , sometimes even up to 1,000°C,” Patel said. “And we’re still able to see stuff down to the atomic scale and deduce fundamental phenomena.”

One of the main instruments Patel works with is the low energy electron microscope (LEEM). This instrument uses reflected low-energy electrons to create a real-time image of atomic processes on a material’s surface.

Patel and Zhou have used LEEM to investigate problems such as the initial stages of metallic corrosion or the impact of carbon monoxide on nickel alloys at high temperatures. The latter is an area Patel particularly focuses on — metals that endure extreme environments and stressors, for which understanding their behavior down to their atoms would be crucial in creating even stronger and better materials. Patel compared the process to assembling sets or builds.

“You’ve got these building blocks and LEGO bricks, and you can put them together however you want, and make whatever you want. That’s how I see materials science,” he said. “You’ve got these atoms, and they behave a certain way, and you can use that information to explore materials and discover new phenomena grounded in solid fundamentals.”

Finding creativity in logic

Patel has always had the eye and mind for physics, enticed by the freedom laden in the logic and laws of the atomic world. As opposed to fields like biology, chemistry or even history, which all require heavy and precise memorization, physics gave Patel the opportunity to get creative.

“Physics, for me, has always been something that flows logically. My brain just works better in that area,” he said. “Materials science is one of those fields where you’re taught how atoms behave, and you know how they interact and how you can probe them and see what they’re doing. You can then use those findings and principles to look into materials for all kinds of applications.”

Patel’s education has taken him many places, as he moved from his home country of Zambia on a journey to advance as far as he could in his scientific studies.

“I do owe a lot of my life and my life skills, per se, [to Zambia] because I grew up over there,” he said. “What is in my head is mostly Zambian in that sense.”

While at Murdoch University, Patel had the opportunity to complete an additional year of pure research, rather than taking conventional classes.

“That is when I realized, ‘OK, this is probably it. You just deal with these giant spaceship-looking things and try to expand in that direction.’ Then, I just kind of did that,” he said. “Once I got hooked on the creative freedom that comes with understanding these materials down to the atomic scale, I decided to come to Binghamton to continue my research journey. It’s been great.”

Beyond gaining the hands-on experience and machine time he craved through working in Zhou’s lab, Patel has also had the opportunity to work with leading scientists at the Brookhaven National Lab’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials and National Synchrotron Light Source II.

Beyond the LEEM, he also specializes in operating machines such as the scanning tunneling microscope, which holds an extremely sharp metal tip a fraction of a nanometer away from a sample to image the atoms at its surface, as well as X-ray diffraction (the same technique used to reveal the structure of DNA), amongst many other advanced techniques.

But it isn’t just the scientific enterprise that keeps Patel drawn to research. It’s also the spirit of collaboration. Whether it’s meeting up with Zhou every Friday to spend hours parsing through the puzzling data coming out of their experiments, or aiding fellow labmates in solving their own questions, Patel said finding community in a field where it’s particularly easy to get stumped on a problem makes the pursuit especially rewarding.

“The science is interesting in itself, but I have particularly enjoyed the collaboration side a lot more. Because that goes beyond the science that I’m doing, in a sense,” he said. “Thanks to Professor Zhou’s guidance and collaborations, I’ve been able to work with a bunch of scientists at Brookhaven National Lab, and they have trained me to essentially operate all these different advanced instruments. Perhaps more importantly, they have taught me how to think like a surface scientist.”

Solving puzzles and problems

As Patel prepares to finish his doctoral studies, he’s interested in potentially entering the semiconductor industry, where the manufacture of these nanometer-sized chips depends on the very fundamental processes he’d been studying.

But between the science of corrosion and atomic behavior, Patel added that the fundamental knowledge he’s gained can apply to many other fields.

“The overall idea would be to continue making meaningful contributions to the field by try to break down these fundamental aspects related to materials, so that they can be harnessed in a better way to get our desired properties,” he said, “whether that be for the semiconductor industry or for the development of more robust materials and so on.”

After spending several years studying materials science, Patel said one of the most valuable things he’s learned from researchers he’s worked with is how to see the bigger picture — even when working with the smallest particles.

“A lot of the time, I’m just trying to figure out why experiments and materials are not behaving how I thought they would behave. I expected it to go down this one path based on previous experience, but I don’t see that. Then you start to wonder why that is the case,” he said. “The whole fun in research is in this iterative process of trying to logically rule out the different possibilities, to figure out what’s really happening at the atomic scale using all the fancy gizmos available.”

It’s this principle that has changed the way he views the world even outside the lab, turning mundane everyday sightings into puzzles to be solved.

“It’s like, ‘OK, how did they tackle this problem?’ Maybe not down to the atomic scale, but at least from a basic materials science perspective,” he said. “What could it be made of and what would you need to do in order to get these kinds of properties out of the material?”

When not wrapping up his school projects and studies, one problem Patel is currently tackling is repairing his own car, among other DIY projects.

“At the end of the day, I’m a son of a mechanical engineer,” he said. “So it runs in the blood.”