Prescription problems: Binghamton University Pharmacy School professors and their students study recent closures of local pharmacies

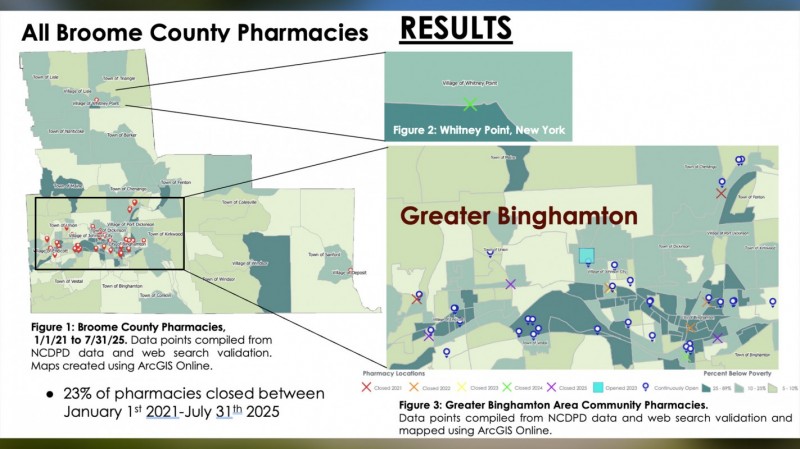

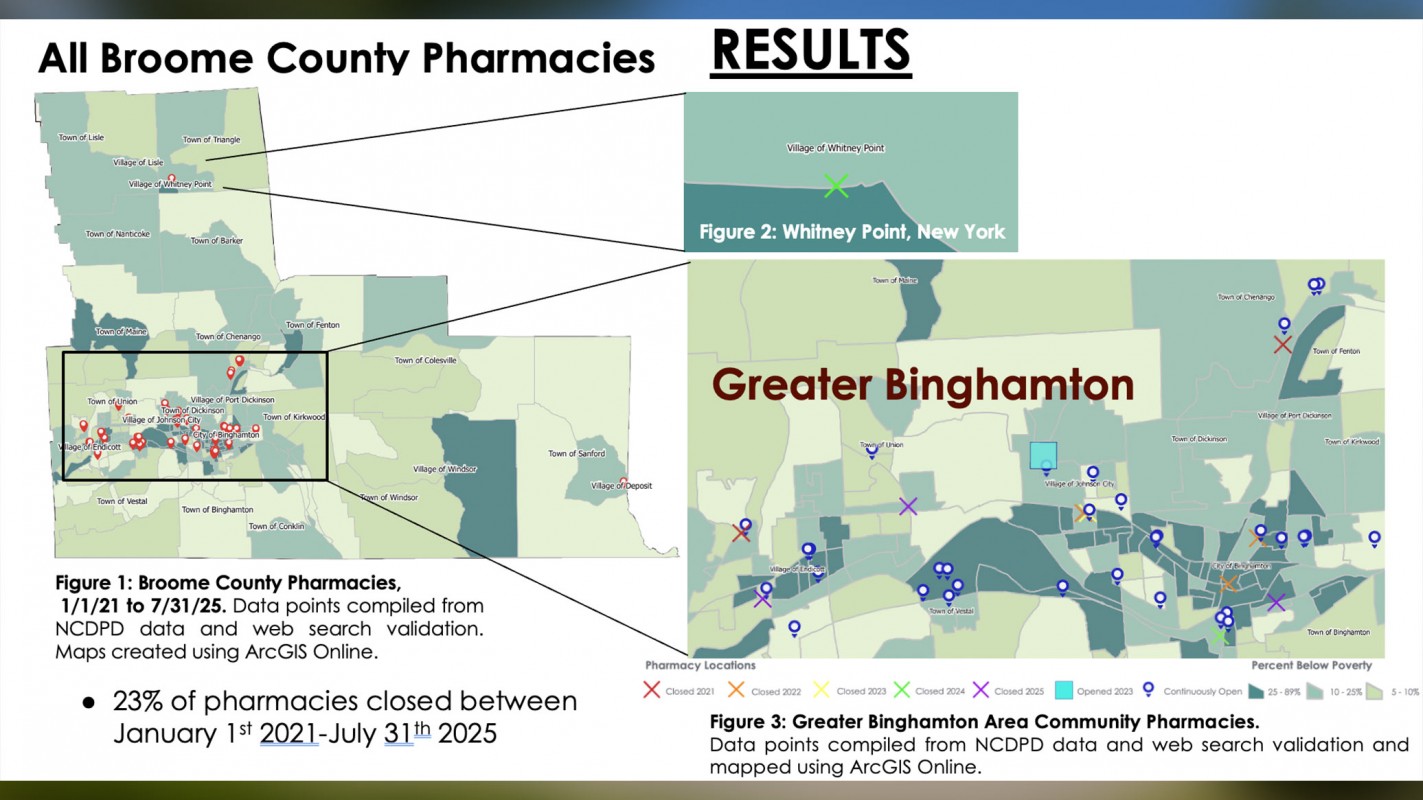

Professors Hageman and Lussier find 23% of community pharmacies in Broome County closed between January 2021 and July 2025

Between January 2021 and July 2025, 23% of community pharmacies in Broome County closed their doors, according to new research from students and faculty at the Binghamton University School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science.

This study is the capstone research project of fourth-year pharmacy students (P4s) Jonathan Korotkin, Cyndy Gallo, Emily Mohlmann and Corey Graziade, who are being guided by Clinical Assistant Professors Elizabeth Hageman and Mia Lussier. Titled “An Analysis of Pharmacy Closures in Broome County and Their Effects on Pharmacy Workforce,” the project investigates not only the closures but also how they are affecting pharmacy staff workflow, morale and patient access.

Mohlmann said some of the goals of this study were to identify where closures occurred, whether they create “pharmacy deserts,” and to understand both staff and community perspectives. She added she wanted to do something that was community-related and might actually help the people who live in Broome County.

“I’ve always done laboratory research, but I felt like this project would let me take a different approach and learn new skills,” she said. “What drew me to it is that pharmacy closures are something that people notice and talk about, but often we don’t stop to ask what those closures mean for the community or for the staff working inside pharmacies. Our goal was to see if recent closures had any measurable effects on pharmacy workflow and on how pharmacy technicians and pharmacists themselves feel about their work. I thought it was important to try to capture those experiences in a way that could inform future decisions.”

Hageman is a Binghamton native, so this study may be a little more personal to her than most. She’s worked at several different pharmacies around the area over the last 20 years, so she’s seen several community pharmacies close their doors — and that got her thinking.

“When our students started discussing capstone project ideas, I thought it would be important to turn our attention to our own community and ask: Where are pharmacies closing, when did they close and what patterns can we see?” she said. “Beyond the numbers, we wanted to know how these closures affect the staff working in the pharmacies that remain open. It’s not just about locations on a map, but about how closures ripple through the system and impact the people involved.”

Feeling the impact

To understand how closures affect pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, the group started surveying pharmacies around Broome County. Mohlmann said the surveys found that most staff who had been impacted by a recent closure reported major changes in their day-to-day work.

“They were dealing with increased prescription volumes, staffing shortages and more patients walking through their doors,” she said. “A lot of their time shifted away from counseling patients and providing direct care. Instead, they were spending more time troubleshooting billing issues, managing inventory or just trying to keep up with the sheer workload.”

Gallo said they asked about was how staff morale could be improved, because burnout often came up in the responses they received.

“Some people mentioned small interventions like employee appreciation events, team lunches or simply being acknowledged for their hard work,” she said. “Those may sound simple, but they make a real difference in how connected and valued staff feel. Of course, we also recognize that those things don’t fix the larger, systemic challenges that come from staffing shortages and profit-driven business models. Still, even small efforts can help boost morale and give staff a reminder that their work matters, especially during times when pharmacies are closing and the workload is heavier than ever.”

But why are all of these pharmacies closing? That’s the question on everyone’s mind. Hageman said the biggest theme that came out of their surveys was the profit-driven model of pharmacy.

“These are businesses, and decisions about which stores to keep open and which to close often come down to finances,” she explained. “Pharmacies that aren’t meeting quotas for vaccines, compliance or profitability are the ones that companies may decide to shut down, regardless of the needs of the community. Staff working in those pharmacies see firsthand how these business decisions impact patients, but they don’t have a say in the process. It’s a sobering reminder that healthcare access can be determined by profit margins as much as by patient needs.”

Hageman added that while the pharmacies may be closing, there is still a high demand for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.

Walking through the desert

Another goal of this study was to identify whether these closures have created a “pharmacy desert” in Broome County. Based on a published study, Hageman and her students defined “pharmacy deserts” as census tracts that met both low-income and low-access criteria:

- Low income: ≥20% below poverty or median income <80% of nearby metro area.

- Low access: ≥33% of residents live beyond distance thresholds (1–10 miles based on urbanicity and car ownership).

Tracts were categorized as urban, suburban, or rural using population density per established standards.

One of the assumptions Hageman had going into the study was that after closures in downtown Binghamton, they were going to see a “pharmacy desert” there. But after looking at the data, mapping which pharmacies are still operating and applying the formal definition, it didn’t meet the criteria.

“That was surprising because on the ground, it really feels like those closures have left a gap,” Hageman said. “What we did find is that there are some rural areas, like Whitney Point and Windsor, that might qualify as pharmacy deserts because of the distance people have to travel for care. So while the data tells one story, the lived experience and the staff perceptions tell another, and both are important to understand.”

Gallo emphasized Hageman’s statement that even though Broome County as a whole doesn’t qualify as a pharmacy desert, the community still feels the impact when pharmacies close.

“People notice longer lines, more crowded pharmacies and staff that seem stretched thin,” Gallo said. “It creates this perception that access is harder, even if technically there’s still a pharmacy within a defined distance. The word we kept coming back to was ‘felt’—these closures are felt in a real, emotional way by patients and staff. That’s important because healthcare isn’t just about statistics; it’s also about how people experience access and how confident they feel about getting the care they need.”

Personal connection

While the first phase of the research has really focused on the pharmacy staff perspective, they want to look at the personal impact these closures are having.

Hageman said they want to turn to the patients themselves, especially seniors over the age of 65, and ask how these closures are affecting their lives. “Are they having trouble getting refills on time? Do they feel like they’ve lost continuity with a trusted pharmacy? Or are they finding ways to adapt? We’re going into that phase with an open mind, because it’s possible that patients are more resilient than we think, or it’s possible that these closures are creating real barriers to care. Either way, it’s crucial to listen to their voices before we start talking about solutions.”

Mohlmann said that due to many of the closures, they found that many pharmacists were losing that personal connection to their patients that comes with being a community pharmacist.

“These changes take away from the human side of pharmacy, because the more time you spend putting out fires, the less time you have to build relationships with patients. Many respondents also talked about stress, burnout, and frustration with a system that felt like it was working against them rather than supporting them.”

For residents who live in low-income communities, it can really create a ripple effect.

“A lot of patients in those communities may not have reliable transportation, so suddenly they’re forced to travel much farther just to get their prescriptions filled,” said Gallo. “That extra burden can mean people delay or even skip their medications, which only worsens health disparities. It’s not just about convenience — it’s about equity and access to care.”

After decades of service in healthcare and seeing how pharmacy closures can impact local communities, Hageman is hoping this trend turns around soon.

“If the nearest pharmacy is miles away, and you don’t have reliable transportation or childcare, you’re left with almost impossible choices,” she said. “Do you spend your limited money on a cab or bus fare to get your medication, or do you put that money toward groceries and bills? Those are the tough trade-offs people in these communities are forced to make.”

While Hageman and the students are still investigating solutions on how to stop any future closures, they agree that currently the best solution is assisting patients by finding what works best for them and help them navigate this ever-changing pharmacy landscape.