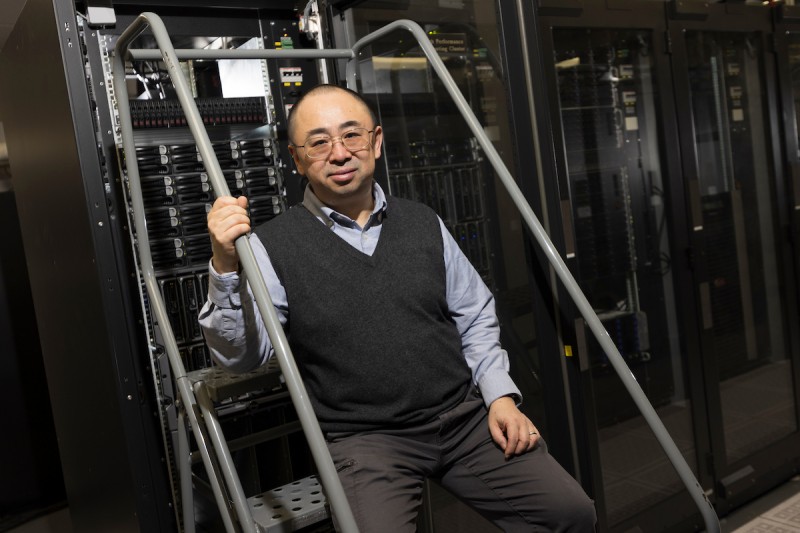

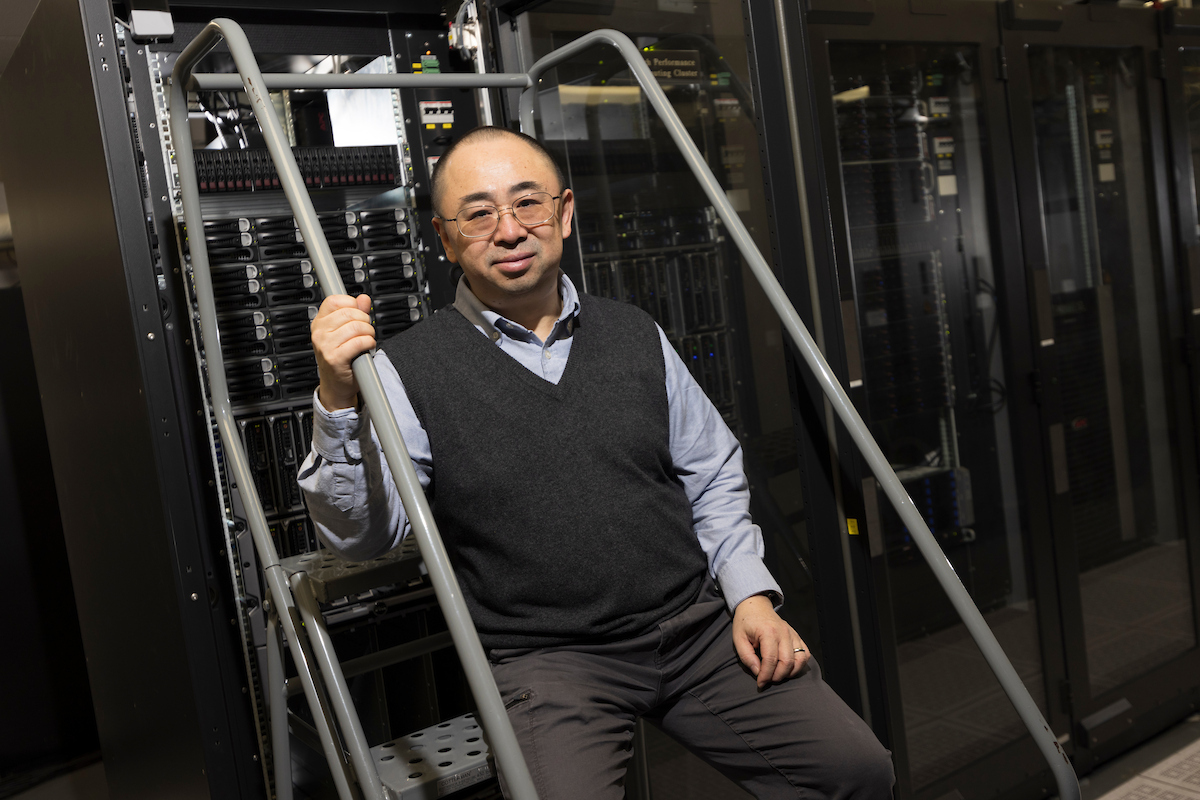

Professor wins grant to accelerate deepfake detection research

Yu Chen’s technology detects AI-generated content through 'fingerprints'

Six-fingered hands and asymmetrical eyes no longer comprise the common red flags of an AI-generated photo.

As generative AI continues to advance, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to discern whether that image, video or even audio on your social media feed has been made by a machine. But technology being developed at Binghamton University could enable the next generation of AI detectors to catch up to their generative counterparts.

Yu Chen, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science, recently won $50,000 from the SUNY Technology Accelerator Fund (TAF) to support the development of his technology, which uses environmental “fingerprints” and data to flag AI content and deepfakes, rather than visible tells.

“Our work is based on a different philosophy: We do not look into the content of the image, video or audio. We look at the invisible features embedded into that multimedia, which are generated by the device used to shoot the video or audio, like a camera, camcorder or microphone,” he said. “Those things, when they make such a record, naturally embed some of what we call an ‘environmental fingerprint.’”

Take, for example, a recording of a Zoom meeting. That camera and mic will not only capture your image sitting in front of your computer, but also the invisible electromagnetic signals filling the room — noises which can only have occurred at that specific time and location.

“If we shoot a video right here and now, one of the environmental fingerprints we’re talking about is called the electrical network frequency (ENF) signal,” Chen said. “That is the fluctuation introduced by the power grid, which is unique and unpredictable.”

As real as AI-generated video of a person taking a morning meeting may look, it cannot fabricate an exact match of the environmental fingerprint that would be expected from a real recording of an actual person taking an early call at their desk. Right now, no AI generators can synthesize such a fingerprint accurately.

“They cannot predict what the fingerprint will be at a certain place, at a certain moment. However, they can create a fingerprint that appears genuine or use a fingerprint obtained from earlier media. They can embed that into the media they are generating,” Chen said. “However, that fingerprint still does not match what they claim to be the time and location.”

Chen began developing this technology in 2018, while his team was exploring potential tools to fight against deepfake attacks. Now, through the TAF grant, which helps accelerate the process of bringing academic innovations to market, his team plans on leaving the controlled lab environment behind and taking on the much messier realm of real-world data.

“The SUNY TAF grant is such an important accelerator to help us bridge the gap from the lab to the real world, to make our work really contribute to society,” Chen said. “It’ll help it really be applicable to normal people in their daily use. Or, we can even help law enforcement, digital forensics or intelligence operations to detect or identify whether a piece of media is AI-generated or from an actual camera.”

To test their technology on real-world data, Chen and his team will use information that has already been amassed by other researchers in the public domain, while also generating hundreds of thousands of images, videos and audio on their own. He hopes to cover most of the popular AI generators in use today, and he will be collaborating with academic and industry partners, including social media companies.

“Our technology is not to replace machine learning or AI-based detection. It’s an important complementary technology,” he said. “For some angles that AI or machine learning-based solutions cannot address, we can provide a solution.”

Furthermore, AI-based solutions can also be heavyweight and expensive, relying on powerful servers to work. Chen’s detector — called CerVaLens — is much lighter and cheaper, with an initial version already developed for Google Pixel 10 smartphones. Through TAF funding, he hopes it will eventually join other mobile devices as an app that anyone can download on their phones to check if something has been AI-generated.

He imagines that as technology and AI proliferate, this detector could find many other uses beyond social media.

“Now, we are facing the time of AI penetrating almost every area of our lives. I even expect that one day, our technology could be used to connect the virtual and physical world — like if you looked at something like Metaverse, remote education or remote healthcare,” he said. Doctors who rely on cyberspace to consult with patients could use his detector to ensure patient information and data haven’t been tampered with through AI.

Chen originally worked in network security on the Internet of Things or smart cities. But over time, he noticed that the definition of “infrastructure” and security was changing to encompass AI content as well — including its drawbacks and potential misinformation.

“If the information itself is fake, the decision-making is going to be misled,” he said. “That’s the main motivation and turning point I had to switch from the physical network infrastructure to digital ecosystem infrastructure.”

Chen is excited to keep advancing his own technology through SUNY’s TAF grant.

“Although many people enjoy the advantage of AI — the convenience, the high efficiency — we’ve got to be aware of the potential risks with those advanced technologies playing a more and more important role in our daily life,” he said. “That’s the most exciting thing to me [about receiving the award]. That means our vision has been recognized by the community.”

He added, however, that while technology experts are growing to recognize the risks of AI-generated content, the average person might not. Providing the proper tools and access to be able to tell the difference will be critical, as the landscape of the internet continues to change.

“People deserve to know if what they are looking at is from the real world or AI-generated,” he said.