Cross-Cultural Theater Exchange: The Search for Aesthetic Affinities

YIN Xiaodong

Across the globe, different cultural traditions nurtured diverse theatrical forms. In the cultural development trajectory of each individual nation, art forms as distinct as India’s Sanskrit drama, China’s xiqu (traditional Chinese theater), Japan’s kabuki, and Korea’s pansori emerged. Once the shared significance and aesthetic affinities among these varied traditions can be identified, the extraordinary power of theater to transcend national and linguistic boundaries can be unleashed. Stage art continues to evolve through international theater festivals, overseas touring performances, international collaborative productions, and talent development programs, infusing the world culture with fresh vitality.

At the heart of cross-cultural theater exchange lies the imperative to find common ground in the values and ideals that theater seeks to convey. The year 2012 marks the twentieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and South Korea. I had the privilege of leading the China National Peking Opera Company (CNPOC) to the National Theater of Korea in Seoul, where we presented the classic of the Cheng School in jingju (Peking opera), Suolinnang (The Jewelry Purse). This performance was a departure from past practices. Conventionally, international jingju tours would mostly select plays that showcase performance and martial arts skills to overcome language barriers and avoid alienating the audience. In contrast, Suolinnang, with its abundant singing and spoken lines, is a literary drama that focuses on its twists and turns in plot and the ups and downs in characters’ lives.

Suolinnang stands as one of the signature works of jingju master Cheng Yanqiu. The Cheng School’s singular vocal stylings and performance traditions portray the nuances of human kindness and cruelty and evoke the life philosophy that virtue is built through good deeds. Before our departure for Korea, we found ourselves wondering: could the values at the heart of this play truly resonate across borders in an unfamiliar cultural context? On the night of the performance, seated quietly among the audience, my gaze shifted constantly between the stage and the auditorium. When I saw the Korean audience responding genuinely to the unfolding plot, engaging with the fates of the characters, my anxieties melted away: Suolinnang speaks beyond the borders. Its themes—generosity, moral righteousness, helping those in need, and repaying kindness—find a natural home in the hearts of Korean viewers, as well as in those of audience from the rest of the world.

To ensure that the Korean audience can fully engage with the play, we invited a renowned Korean sinologist to translate the script prior to our departure. Back then, Shen Xiaogang—then Cultural Counselor at the Chinese Embassy in Seoul—and his father meticulously reviewed and revised the translation. Their efforts ensured the accurate delivery of the lyrics and spoken lines, removing any language barriers in cross-cultural theater exchange. The theater ended up having a full house on both nights of the performance. The success of the Chinese jingju Suolinnang on the Seoul stage offered compelling evidence that the ideals of truth, kindness, and beauty are shared across cultures. From this, we found a fundamental aspect of cross-cultural theatrical dialogue: the transmission of the core values embodied in theatrical art. Furthermore, we discovered a viable pathway through practice, the identification of aesthetic affinities among diverse theatrical traditions.

The theatrical exchange between China and Japan has a long and rich history.

In recent decades, this legacy has been deepened through vibrant exchanges and joint

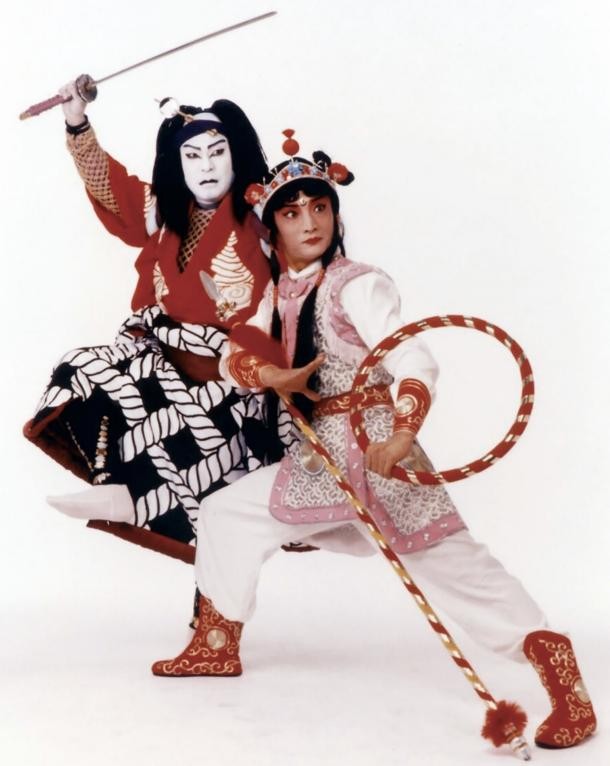

productions by close collaborations between theater artists from both nations. Jingju and kabuki are the traditional theatrical forms of China and Japan, respectively. Jinju features

powerful, high-pitched vocalization, while kabuki is known for its slow and melodic

singing. In the 1980s and 1990s, renowned Chinese jingju artist Li Guang collaborated with Japanese kabuki artist Ichikawa Ennosuke III to jointly create the jingju–kabuki hybrid production, Longwang (Ryū-Ō, Dragon King). The script for the play was co-written by Chinese playwright

Lü Ruiming and Japanese playwright Nakawa Shōsuke. The main characters include Nezha,

who is of Chinese origin, and Umihiko, a character of mixed Chinese and Japanese descent.

The creators of Longwang undertook a meaningful exploration of aesthetic convergence,

fusing the strengths of jingju and kabuki into a singular theatrical experience. At

the time, Longwang set a remarkable record of one hundred consecutive performances

in Japan—a milestone that inscribed a luminous chapter in the history of Sino-Japanese

cultural exchange.

Building on this success, Li Guang later adapted the beloved Japanese classic Sakamoto Ryōma for the jingju stage. Sakamoto Ryōma, a revered national hero in Japanese cultural memory, was reimagined through a production that blended signature elements of kabuki, such as swordplay and dance, with the dynamic martial artistry of wusheng (martial artist) roles in jingju. The resulting work honored the characteristics of Japanese theatrical tradition while preserving the distinctive performative styles of jingju, achieving a harmony between two distinct stage cultures. It stands today as a gem in the ongoing story of Sino-Japanese theatrical exchange. When the convergence of values and the aesthetic affinities are identified, they form the two pillars necessary for the successful transmission of theatrical art. In addition to this foundation, the creation of an enduring mechanism and platform is also essential to sustaining theatrical exchange.

Since 2001, the National Peking Opera Company has embarked on more than a decade of close partnership with the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries and Japan’s Min-On Concert Association. In addition to showcasing its traditional repertoire, the National Peking Opera Company developed two productions specially tailored for Japanese audiences: Jugongjincui zhuge kongming (Zhuge Kongming: A Life of Dedication), inspired by the Sanguo yanyi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), and Sihai zhinei jie xiongdi (All Men Are Brothers), drawn from Shuihu zhuan (The Water Margin).

Together, the two plays have been staged more than two hundred times in almost all the prefectures and cities in Japan. They offered the Japanese audience not only a vivid experience of the art of jingju but also a window into China’s classical literary tradition.

Building platforms for children’s theater exchange is another important cornerstone for the future of international theatrical exchange. The China National Theatre for Children (CNTC), where I once worked, has undergone vibrant exchanges in the field of children’s theater. Every year, practitioners of children’s theater from China, Japan, and South Korea meet at events such as the China Children’s Theatre Festival, Ricca Ricca Festa (International Theater Festival OKINAWA for Young Audiences) in Japan, and ASSITEJ Korea’s international theatre festivals, where they perform classic productions. The China National Theatre for Children also purchased the copyright and adapted the Bian Bian Bian (Transformations) series of children’s plays from Japan’s Dougeza Drama Company. Today, the Bian Bian Bian series has become one of the most popular long-running staples of the China National Theatre for Children’s repertoire.

As China’s premier institution for Chinese xiqu education, the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts (NACTA) has opened its doors to international students since the 1980s. Over the decades, it has trained thousands of international graduates. Among them, Ishiyama Yuta of Japan, Lee Kwang-Bok of South Korea, and Gundmann of Germany have gone on to become influential ambassadors for Chinese xiqu and leading figures in the fields of international theater, music, and cultural exchanges. In addition, the Academy has also collaborated extensively with artists across the globe, producing works such as Da dunhuang (The Great Dunhuang), Baishe zhuan (The Legend of the White Snake), Yeying (The Nightingale), and Wangzhe edi (Oedipus the King).

Over the years of practice, we have seen how exchanges between Chinese and international theater artists, alongside their audiences, have expanded perspectives and forged lasting emotional ties. The old saying, “what is national is universal,” finds vivid manifestations in these experiences. Theater has proven to possess a remarkable ability to transcend mountains and oceans, to overcome the barriers of language and borders, and to weave together the luminous tapestry of human civilization.

(Author Yin Xiaodong serves as the President of the National Academy of Chinese Theatre Arts, Vice President of the China Theatre Association, and Professor.)

This article was first published in Chinese in Guangming Daily in 2024.

Yin, Xiaodong. “Cross-Cultural Theater Exchange: The Search for Aesthetic Affinities.” Guangming Daily [Beijing], 3 Jan. 2024. 16.

The English translation of this article was published in the second volume of TheaComm, an E-Journal of Theater Arts Communication, in October, 2025. DOI.org (Crossref), http://doi.org/10.22191/theacomm/volume2/article3.

Translator: Yanhui Jiang

Proofreader: Chenqing Song, Xi Wang