Image as object: Professor’s work explores the changing nature of photography

In the days of the smartphone, photography has become ephemeral — a matter of pixels created, manipulated and then shared on a screen.

Of the estimated 1.5 trillion photographs created annually, some linger, perhaps shared on social media or even printed out by someone with an old-school photo album. But many simply vanish, deleted just as quickly as they were created. It’s a far cry from the early days of the daguerreotype, when somber photographic subjects stood stock-still as light etched their image on silver-plated copper, preserved for the ages as family heirlooms.

Associate Professor of Art and Design Hans Gindlesberger is exploring the changing nature of photography — from physical to immaterial — in “Blank______Photographs,” a constellation of multi-media projects. He has received a prestigious Light Work Grant in Photography for the endeavor, which will be featured at an upcoming exhibition.

Founded in 1973, the artist-run nonprofit is housed in Syracuse University’s Robert B. Menschel Media Center. The Light Work Grants program, which dates back to 1975, is one of the longest-running photography fellowships in the country. Recipients receive a $3,000 stipend, exhibit their work at Light Work and appear in Contact Sheet: The Light Work Annual.

“Blank______Photographs” is comprised of four projects, each very different in technique and appearance, but all connected by an investigation into the materiality of photography. Each uses unconventional, photo-adjacent processes such as 3D scanning, paper casting, glasswork or crayon rubbing to look past the image and toward the photograph’s physical presence or into its digital code.

Some of the projects in the portfolio are essentially complete, while Gindlesberger is currently working on others for the fall exhibition — although whether that show can take place physically is an open question due to the pandemic.

“It’s definitely an ironic twist for this work that was made with the express purpose of not being virtual,” he observed.

Light Work has been a vital organization within the photography community for decades, Gindlesberger said, and many of the artists whose work he has admired have either been through its residency program or featured in its publications.

“Teaching at Binghamton, it’s an incredible benefit to have such a pillar of the photo community located right in our backyard and to be able to point to that as a model and have all that they do accessible to our students,” he said.

The digital world

Gindlesberger stumbled on the idea for the project after a long stretch filled with shows around the world, which he never had the opportunity to see in person. Instead, he either shipped his work out or emailed the files to international venues, which then printed them out.

“As an artist, it was disorienting to go for a year where I didn’t have to frame and ship work, or be present for an installation or get to see people interact with the work,” he reflected.

The experience sparked a question: What gets lost when we create, view and share our photographs only in the digital realm?

“We are creating more pictures than ever — trillions a year — but with that there’s an entirely different paradigm for how we interact with images and how images act on us. That’s not to say there’s any more or less value in one or the other, but I was interested in what stories could be found on the material plane of photographs and in our tactile relationship with them,” he said.

The four projects don’t look like conventional camera images, but rather as esoteric, even illogical, art objects.

One of the projects in the series, “A Photographic Timeline,” collects specimens of each major iteration of the photographic process. Gindlesberger then makes a crayon rubbing of the surface of each image, providing a tactile index to the evolution of photography.

One challenge: trying to find a specimen of the heliograph invented by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who used bitumen of Judea as the light-sensitive material to create the oldest known photograph in 1827. While vintage plates don’t exist outside of museums, Gindlesberger found someone who recreated the toxic process using material extracted from the Alberta tar sands.

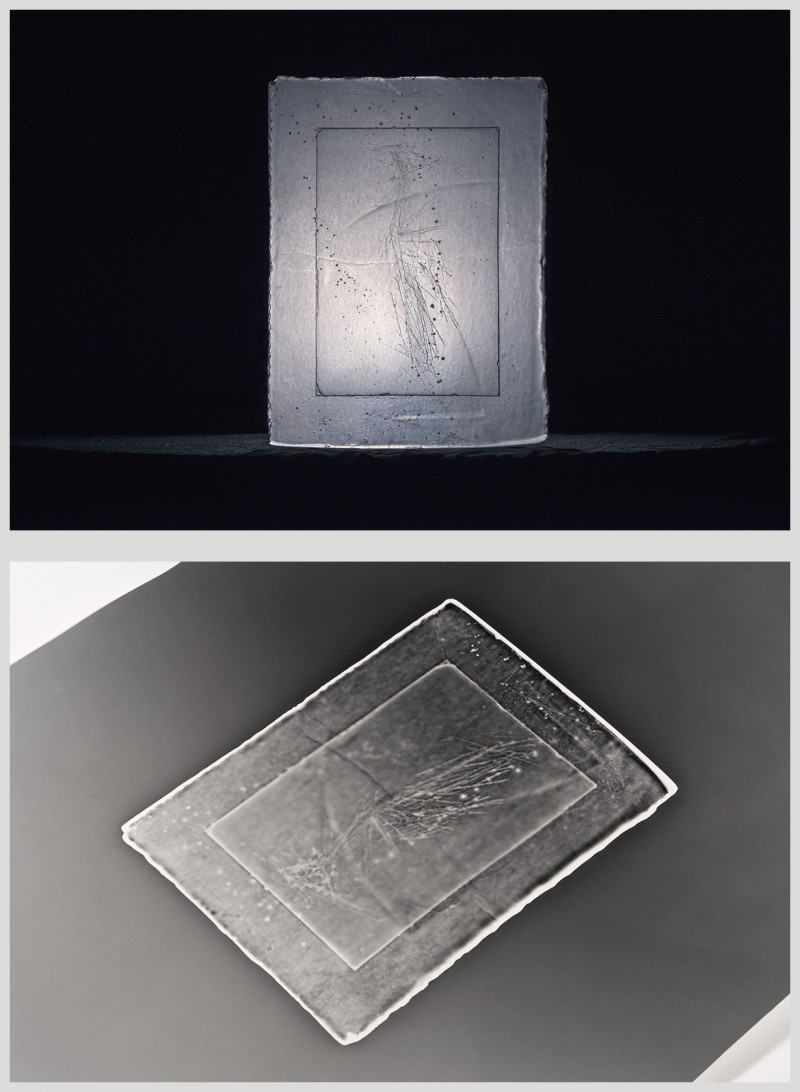

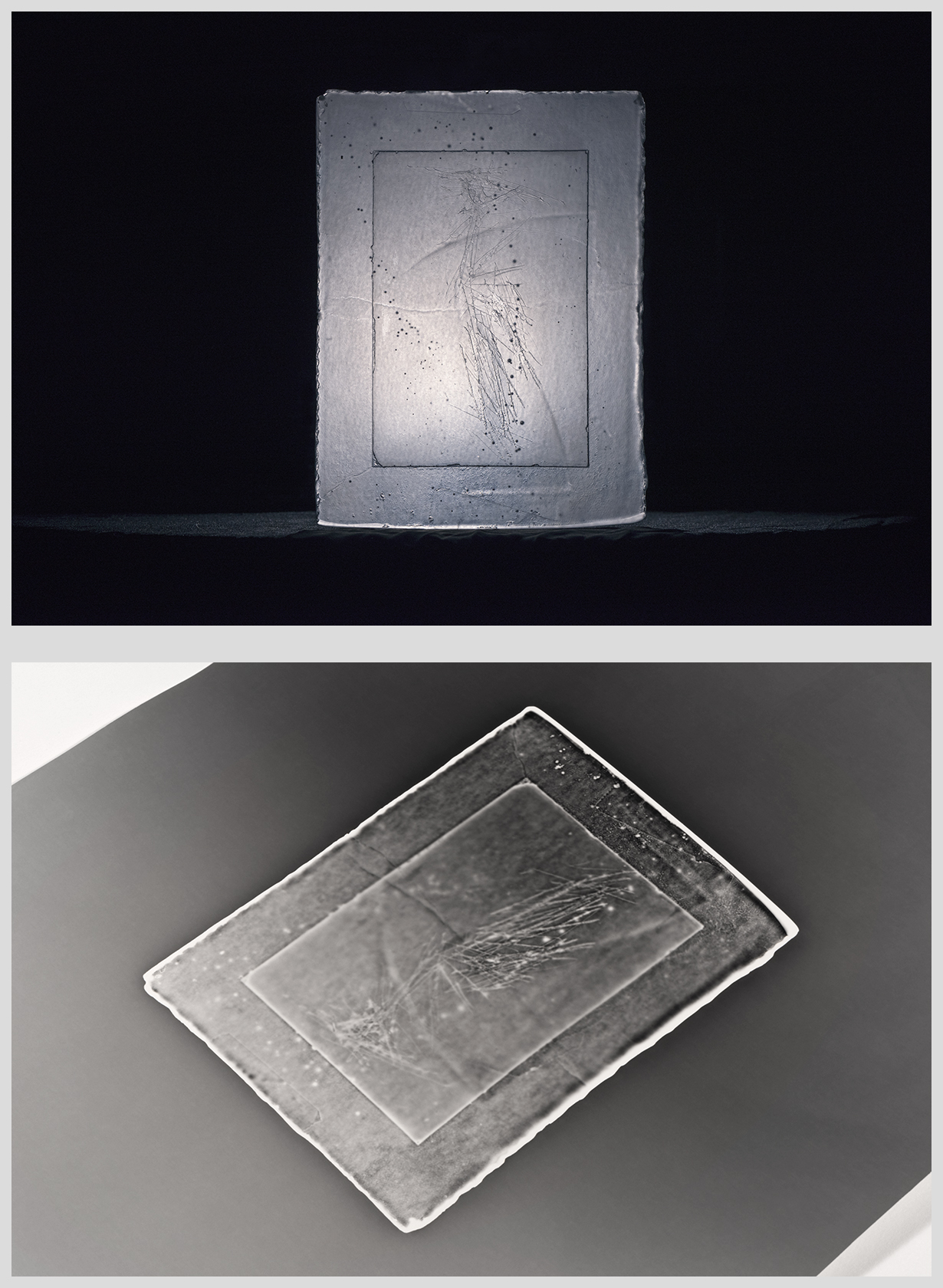

Another of the pieces, “Glass Plates/Double Negatives,” received support from a Harpur Faculty Research Grant in 2019. The grant allowed him to collaborate with a Brooklyn glass artist who had the specialized skill set needed to fabricate thin glass castings of photographs — something that Gindlesberger couldn’t have done himself. The Harpur funding was instrumental in getting that project off the ground and more, since “Glass Plates/Double Negatives” lay at the heart of the portfolio he sent to Light Work.

For Gindlesberger, the most interesting period in photography came in the mid-1800s, which was marked by “a habitual and chaotic process of always becoming something else.”

“I try to bring that spirit forward in thinking about how emerging technologies can alter the production and conception of photography today,” he reflected.