In the lab: Harpur alumna helps develop Pfizer vaccine

When your turn comes to roll up your sleeve for the coronavirus vaccine, take a moment to consider the countless hours that went into its creation. Teams of scientists worked around the clock to analyze the virus, find ways to provoke the immune system’s response, and test its efficacy and safety.

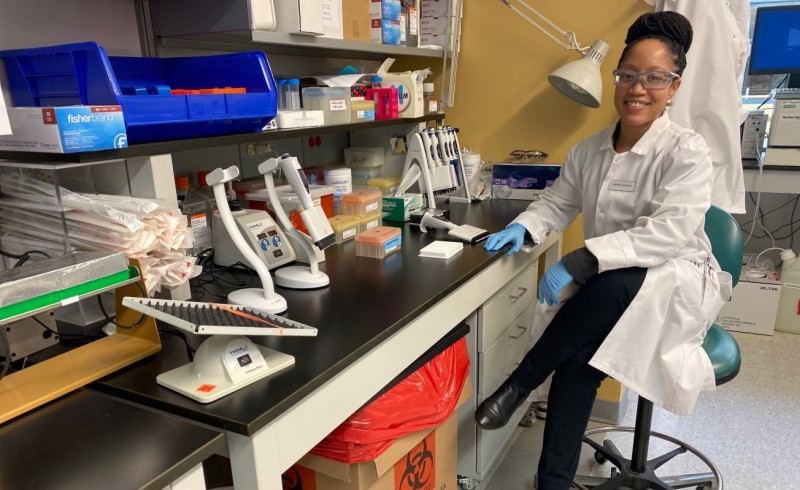

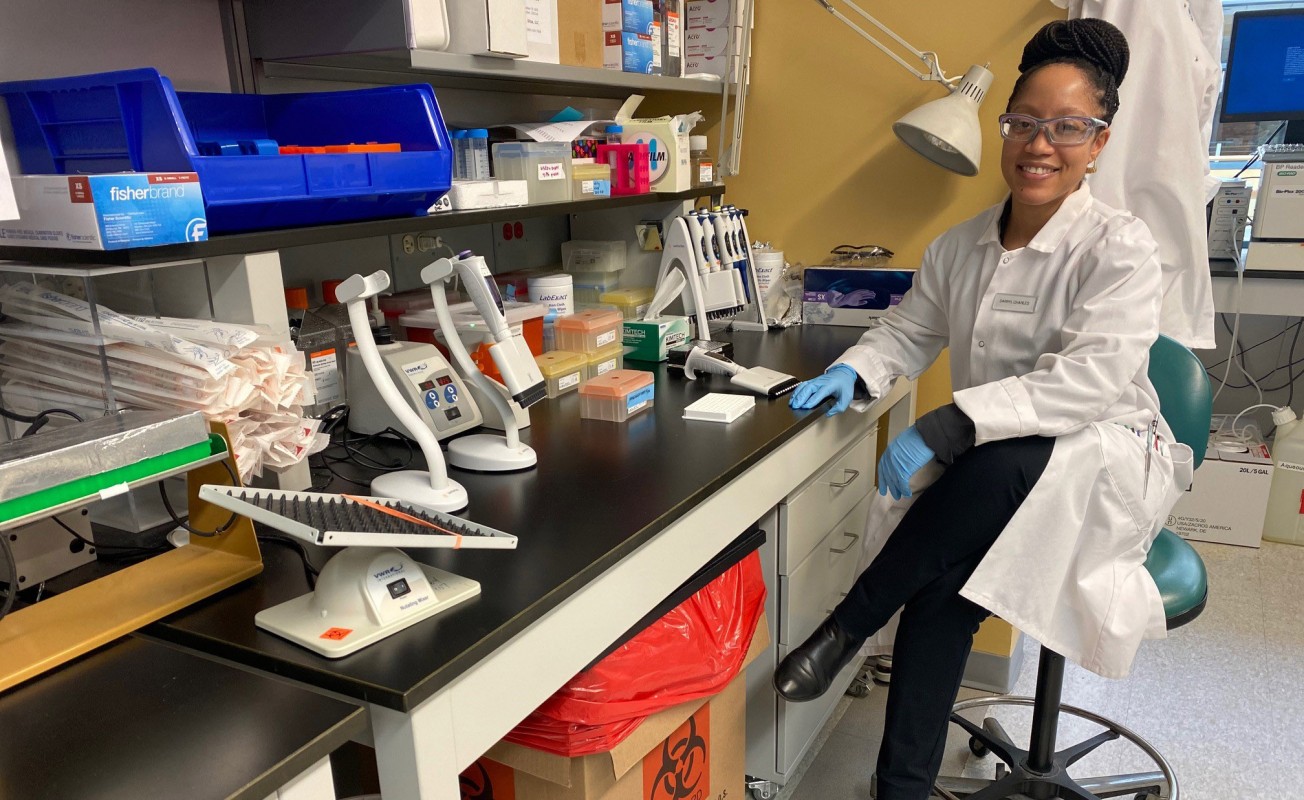

Among them is Harpur College alumna Darryl Melissa Charles, a vaccine research and development scientist at Pfizer working in the assay development group. In layman terms, she and her colleagues measure antibody responses to the vaccine in a sample of blood serum.

“It makes me really excited when everyone tells me that ‘I got the Pfizer vaccine.’ It’s a sense of pride. It’s a great feeling,” said Charles, who graduated from Binghamton University in 2012 with a degree in cellular and molecular biology.

Vaccine development wasn’t initially on Charles’ career radar. She grew up and still lives in Rockland County, which is a melting pot of immigrants from all over the world, including a sizable Haitian community of which she is part.

“Growing up, it was always the typical, ‘So you’re going to become a doctor or a nurse or a lawyer.’ I had no idea that being a scientist was something that I could do,” she said.

Her Binghamton experience

Charles initially opted for Binghamton University for practical reasons: its reputation as a SUNY school and its pre-med track, which suited her high school dream of becoming a doctor. It was also an ideal distance from home: far enough away for the full college experience, but close enough to visit her family.

As the science of life, biology is a broad field. While Charles’ studies largely focused on the cellular and molecular level, she had the opportunity to explore other aspects of the biological sciences in a wetlands ecology course, which involved trekking through the wetlands in the University’s Nature Preserve.

She first became involved in research under Associate Professor Claudia N.H. Marques, joining her lab as a student. Undergraduate research, of course, differs significantly from the pharmaceutical world: projects are smaller, and students typically don’t have access to the same type of equipment or physical resources. But the scientific principles remain the same, and so, too, does the spirit of inquiry.

“I definitely think that set up my love for working on a lab bench,” Charles said of her undergraduate years. “The little experiences definitely did help in migrating me toward this field.”

In addition to Marques, other Binghamton faculty and staff made a major impact on Charles. They include academic counselor Joanna Cardona-Lozada at the Educational Opportunity Program, then the coordinator of the Binghamton Success Program at the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP). Cardona-Lozada proved a ready font of advice from study tips to engaging with professors, giving Charles the opportunity to grow as an individual.

“There was never a doubt that Melissa Charles was going to make a great impact on the world,” said Cardona-Lozada, noting that Charles would frequently stay after class to ask about research opportunities, internships and other Binghamton resources. “She was a mover and a shaker seeking to empower herself with the necessary tools beginning with her freshman year, when I first met her.”

As a student, Charles was one of the founding members of Power United Ladies Striving to Elevate (PULSE).

“I ultimately ended up loving my experience there. I honestly say it to everyone: I had the best years of my life at Binghamton, and I met a lot of the closest friends I have today when I was there,” Charles said.

Becoming a researcher

After graduating from Binghamton, Charles’ future plans shifted slightly to dentistry. She began both applying to dental schools and job-hunting after earning her master’s in biomedical sciences at Rutgers University.

A recruiter reached out to her, and she landed a gig as a contract worker in Pfizer’s oncology division five years ago. After a year, she transitioned into a permanent position in vaccine research and has been there ever since.

“I loved it here so much, I ended up just staying,” she said. “Everything happens for a reason.”

Enter the ultimate unexpected turn: a global pandemic. When New York’s lockdown began, Charles drove through eerily empty streets on the way to work. It reminded her of scenes from the apocalyptic film I am Legend. But once through the doors, the laboratory was “business as usual, with an asterisk,” she said.

As always, deadlines had to be met and the science had to be sound. Any resource they might need was put at their disposal, even if it had to be trucked in from another part of the country.

As scientists, their own resources were also poured into the vaccine effort: six- to seven-day work weeks, coming in early and staying late. The experience deepened Charles’ relationships with her colleagues, who needed to rely on and trust each other to complete an urgent task: the development of a viable vaccine.

“It really puts everything that you’ve already learned to the test,” she said. “Every virus is different. Every protein and every polysaccharide has its own trials and tribulations, but you develop a broad knowledge base and you’re able to apply what you’ve learned in order to get through things.”

Learning that she played a part in the development of the vaccine, her friends and family responded with both pride and curiosity. Charles takes her role as an educator seriously, pointing people to articles and studies that can answer their questions about the vaccine.

“Looking back, I’m still amazed at the pace that we were able to work and maintain scientific integrity. It gives you just that much more of an appreciation for science,” she said.

She is an educator in other ways, too. Sometimes people are surprised to learn that she is a scientist. They often have an image of what a scientist looks like in their minds — someone like Albert Einstein, perhaps, Charles reflected.

But scientists can and do come from a wide range of backgrounds, including Rockland County. She had the opportunity to share that message with fourth-graders at her old school, talking to them about careers in science.

“They’re like, ‘What you did is so cool. I can’t wait to be a scientist!’ It warms my heart because there’s that whole feeling of, ‘Wow, now being a scientist is cool,’” she said. “It opens up the door for these kids who didn’t know that this was a possible career route, something that they could eventually see themselves doing. And it’s important to have that diversity in every field.”