A Preliminary Exploration of the Early 19th Century Chinese Export Paintings Collected in Britain: While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father as a Case Study

CHEN Yaxin

Abstract:

Forty-six Chinese export paintings produced in the 19th century were collected in the British Library and the British Museum. These paintings were created based on performances of 39 Chinese operas. Taking While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father, one of the paintings, as a case study, the article argues that it was drawn based on the Fuchuntang edition of the Chinese opera A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey that should be the Kun opera performed by an extra-Guangzhou Hunan troupe. A critical analysis of the painting and its corresponding opera can be of great help for the exploration of various editions of the opera, the history of Hunan opera, and the history of Guangdong opera. A comparison of the opera costumes and props produced in the period under Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1735-1796) and Emperor Jiaqing’s reign (1796-1820) present in the painting and those reflected in the opera costumes and opera paintings produced in the later period of Qing Dynasty reveals that the styles of opera costumes and props have evolved from simplicity to sophistication, which can shed light on today’s research on and design of opera costumes and props. Also, these 46 export paintings are reliable archival materials for the interpretation of the “Yabu and Huabu contest” (namely, the contest between the elegant Kun opera and other ordinary forms of operas), “Kun Opera Tradition under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s Reigns” and for the dissemination of Chinese opera-themed paintings internationally, as well as for promoting cultural communication between China and the West.

Keywords: Chinese export paintings, Chinese operas, opera paintings, A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father

Export paintings, also called “western paintings” by professional painters, “Chinese paintings” by foreign customers, “Chinese export paintings” and “China trade paintings” by researchers of western art history in the mid-20th century, have been defined by academia as the paintings that were produced in China’s port cities like Guangzhou and then sold to foreign merchants and tourists between 18th century and the early 20th century. As for those paintings that were collected internationally and not for sale, they were not categorized as export paintings. A significant amount of these paintings exist and a majority of them are collected by institutions around six continents. [1] Except for some oil paintings, these paintings were produced by combining traditional Chinese painting techniques and western perspective drawing techniques. As for their themes, they covered almost all areas of China during that period including politics, economy, military affairs, religion, social life, folklore, natural creatures, and also Chinese opera. [2]

[1] According to Rosalien, there are 123 public collection institutions located in Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania, and North America. See van der Poel, Rosalien, Made for Trade, Made in China – Chinese Export Paintings in Dutch Collection: Art and Commodity, 2016, pp.275-279. Also, in line with records by The Chinese Repository, Chinese export paintings have been regularly exported to South America in the 1850s. See Li, Shizhuang, Chinese Export Paintings 1750s-1880s, Sun Yat-Sen University Press, 2014, p.163.

[2] For basic information and relevant research regarding Chinese export paintings, see Wang, Ciceng et al. “Introduction.” in Selected Chinese Export Paintings of the Qing Dynasty in British Library (Volume 1), Guangdong People’s Publishing House, 2011; Chen, Yaxin. “A Review of Research on Chinese Export Paintings in the Qing Dynasty and Thoughts on Future Research Area.” Academic Research, no. 7.

1. An Introduction to the Early 19th Century Opera-Themed Chinese Export Paintings

In as early as the mid-18th century, there had been Chinese export paintings depicting opera performances exported to the United Kingdom. For instance, a mid-18th Chinese export painting (E. 3017-1921) collected in Britain’s Victoria & Albert Museum displays a scene of an opera performance: In an outdoor venue, a scene from Gushu Raising Troops was being performed (possibly a misspelling of Wushu Raising Troops) on a wooden-structured simple stage. In the scene, an actor, who wore a military outfit and a helmet with double pheasant feathers on it, was holding a pose, a bushy red beard covering his white-painted face; on either side of the stage hung couplets, and on the right side a stand was reserved for a female audience; in front of the stage, there was an open area, in which there were stalls, peddlers and customers on its right and a group of people gambling on its left[3]. A similar opera performance can also be seen in a 1780 Chinese export painting collected in Martyn Gregory Gallery in London in which a group of actors and actresses were performing an Auspicious Routine Play vivaciously[4]. According to the present academia’s discoveries and publications, paintings that displayed opera performances in a systematic and thematic way were those early 19th-century Chinese export paintings collected in the British Library and the British Museum.

1.1 The British Library Collection

The British Library collected 36 Chinese export paintings (Add. Or. 2048-2083) characterizing opera stage performance. They were all watercolors drawn on European paper measuring 54 cm in width and 42.8 cm in height. These paintings had been collected by the India Office Library before being added to the British Library collection in 1982[5]. It was possible that the India Office Library got this batch of paintings through correspondences (currently collected in the British Library with Guangzhou merchants, No. Mss. Eur. D. 562.16). In 1803, the board of the British East India Company wrote to the merchants in the Thirteen Hongs of Canton, ordering a batch of paintings depicting Chinese flora on behalf of the India Office Library. Content with the paintings, two years later, the board wrote to the merchants again hoping to order some paintings featuring various themes. It was probably due to this communication that another batch of paintings was sent to the India Office Library in 1806, among which the 36 opera-themed Chinese export paintings were included. Based on such historical recordings, researchers dated this batch of paintings to around 1800 to 1805 [6], or between the fifth and tenth year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing.

All of the 36 paintings were drawn on the basis of scenes from Chinese operas, including Chao-chun Passing the Frontier, The Story of the Chinese Guitar, Ts’ao Is Allowed to Escape from Hua Yung, Bidding Farewell to his Father to Receive the Seal of Office, K’e Yung Borrows Troops, The Capture of I Cheng-ch’ing, The Mad Monk Scolding the Prime Minister, General Hsiang Taking Leave of his Concubine, Yao Ch’I Is Beheaded by Mistake, Shooting at Hua Yung, The Marriage of Chou Ch’ing, Yu Chi Scolding Ch’uang, The Emperor of Ch’I Weeping in the Palace, Through Friendship Yen Sen Is Set Free, Li Po Going to a Foreign Land as an Envoy, With Only Himself Armed He Goes to Attend the Meeting, Ts’ui Tzu Kills the Emperor of Ch’I, While Drunk He Flogs the God of the Gates, Three Battles against Lu Pu, Wu-lang Rescues His Younger Brother,

[3] For more information, see the official website of the Museum at http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O485916/panel-of-chinese-wallpaper-wallpaper-unknown/.

[4] “An operatic performance outside a village.” gouache, 19 ¾ x 19 ¾ ins. Based on the note that “Collez..e di Gius Vallardi / Milano 1820” on the side of the backing sheet, it can be inferred that the painting was a collection by Giuseppe Vallardi (1784-1863). I thank Dr. Patrick Conner for sharing this information with me.

[5] See Wang, Ciceng, et al, “Introduction.” in Selected Chinese Export Paintings of the Qing Dynasty in British Library, Vol. 1, p.17.

[6] Archer, Mildred. India Office Library, Company Drawings in the India Office Library, London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1972, pp.253-259.

Judge Rao Kung Flogs the Royal Carriage, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father, The Emperor of Wei Is Being Oppressed, Slaughtering His Way through Four Gates, Golden Lotus Lifts the Screen, Yu-chi Shoots an Arrow at Shu, While Drunk He Beats up Those at the Mountain Gate, The Story of a Cabbage-Cutting Knife, Dallying with Feng in a Tavern, Wang Ch’ao Being Initiated as a Sworn Brother, The Fisherman’s Daughter Assassinates Chi, Strings for Musical Instruments for Sale, Beheading His Own Son in the Yamen, Emperor Chien Wen Flogs the Carriage, Chen-ngo Assassinates Hu and K’ang Yin Questioning His Highness[7].

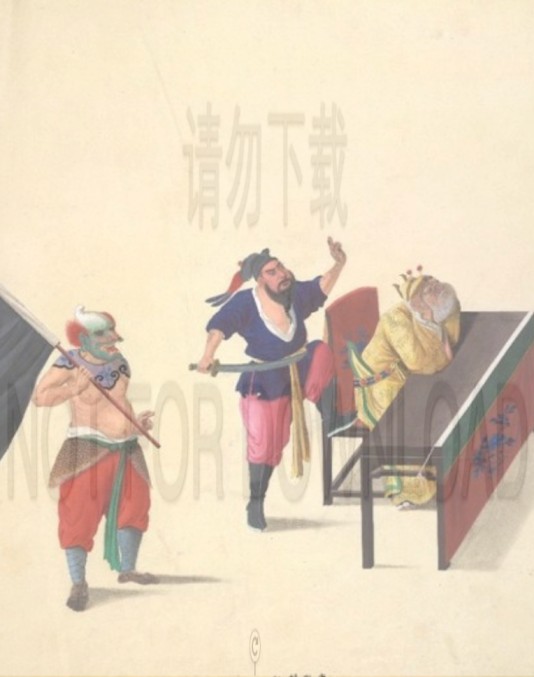

Figure 1: K’ang Yin Questioning His Highness (c), collected in the British Library. The British Library Board (Add. Or. 2083)

1.2 The British Museum Collection

The British Museum also collected a set of 10 Chinese export paintings portraying opera performances during the same period (No. 1877, 0714, 0.819-828); resembling those in the British Library, these paintings were drawn on European papers measuring 53.8 cm by width and 45.3 cm by height [8], among which 7 of them had nearly the same themes as those presented in the 36 paintings. Regarding the difference between these 10 paintings and those 36 ones, the former are ink line drawings rather than watercolors. These paintings were donated by Sarah Maria Reeves (1839-1896) in 1877 among the totally donated 52 albums of variegated drawings, including 1500 export paintings drawn in watercolors. She was born in a naturalist family that had been in relation with Guangzhou historically. Her grandfather

[7] Pictures of all 36 paintings can be found in Wang, Ciceng, et al, “Introduction.” in Selected Chinese Export Paintings of the Qing Dynasty in British Library, Vol. 6.

[8] See the website of the British Museum at http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=270774&partId=1&searchText=opera+painting&page=1.

John Reeves (1774-1856) [9] , worked as a tea inspector in the British East India Company in Guangzhou from 1812 to 1831. During his stay in Guangzhou, he commissioned local painters to draw plants and other specimens of natural history, folk religion, local peoples’ lives and varied occupations, etc. Her father John Russell Reeves (1804-1877) was also a naturalist who lived in Guangzhou for thirty years from 1827. [10] Each painting from this set has the coat of arms of the Reeves family on its lower right corner. [11]

While the British Museum dated these 10 paintings to around 1800-1850 — probably because it is hard to tell whether they had been taken back to the United Kingdom by Sarah’s grandfather or father — I argue that they had been taken back by her grandfather, and therefore their production period ranges from 1800 to 1831 after John Reeves left Guangzhou and never returned. My argument is based on four reasons, as follows. First, these 10 paintings most likely might have been produced during the same period as those collected at the British Library, for their themes, paper material, and size resemble except for one ink line drawing and one watercolor. Second, the European paper had been adopted during 1780 to 1830, [12] and afterwards Chinese paper and papyrus were used for export paintings. Third, a more precise dating of these paintings can be accomplished through the analysis of its quality and realistic features. The export paintings produced during the late 18th century and the early 19th century were high-quality apropos of their painting skills and colors since they were mostly drawn by Chinese painters for their western employers to know about a truthful China. However, since the mid-19th century after the Opium War, westerners did not have to rely on export paintings to gain knowledge about China for they had free access to China and they could take photos in China due to the invention of the camera, which turned export paintings into a kind of souvenir for western tourists. Furthermore, since the invention of the steamboat and other advanced means of transportation spurred tourists’ travel to China, there appeared a tremendous need for paintings. To meet the high demand of paintings by tourists, paintings of identical themes and layouts were in mass production, inevitably leading to low-skilled and gaudy paintings compared to those exquisite ones that had been produced previously. [13] Since the ten paintings display remarkable painting techniques and high documentary value, it can be inferred that they were produced during the late 18th century and the early 19th century, which is close to the period between 1800 and 1831. Fourth, the dating of these paintings can be achieved through a comparison

[9] According to the archival letters between John Reeves and the Thirteen Hongs of Canton and their shipping lists collected at the British Museum, the Cantonese tea traders nicknamed John Reeves “Meishilifu Master” or “Tea Master Reeves”. See Liu, Fengxia. The Port Culture: A Glimpse of the Modern Communication between China and the West through Guangdong’s Export Art, 2012. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Doctoral dissertation, p.127, Fig. 5.51.

[10] See the website of the British Museum at http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=137689; E. Bretschneider, M. D. History of European Botanical Discoveries in China, London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company, Limited, 1898, pp.256-266; Fa-ti Fan. British Naturalists in Qing China, Science, Empire, and Cultural Encounter, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2004, pp.43-45, 164-165.

[11] For coats of arms of the Reeves family, see Liu, Fengxia. The Port Culture: A Glimpse of Modern Communication between China and the West through Guangdong’s Export Art, p.128, fig. 5.53-5.54.

[12] Clunas, Graig. Chinese Export Watercolours, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984, p.77.

[13] Crossman, Carl L. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade – Paintings, Furnishings and Exotic Curiosities, Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991, pp.19, 201.

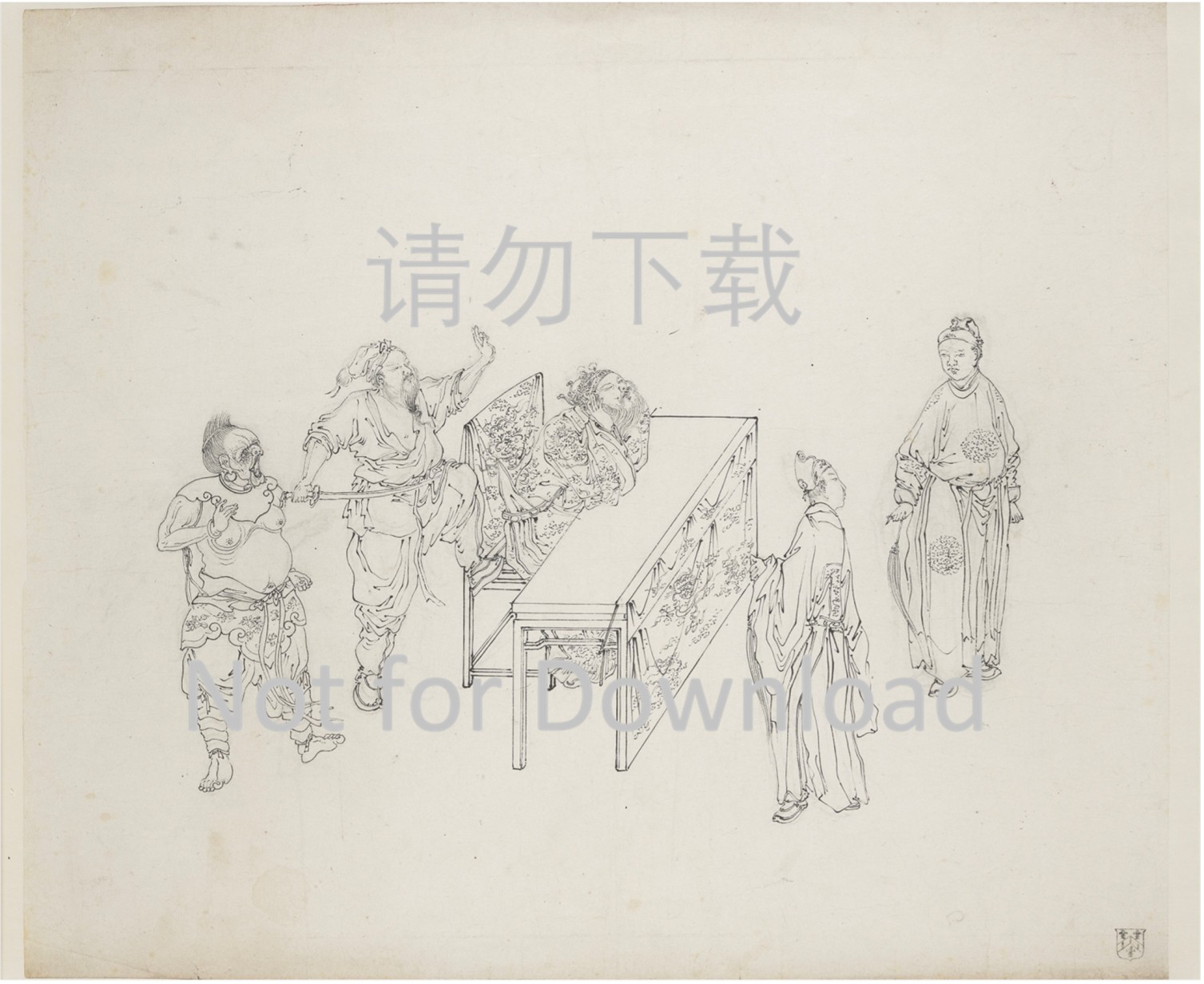

between the two paintings. One (Picture 2), though unnamed, was collected in the British Museum, and the other one named K’ang Yin Questioning His Highness (Picture 1) was collected in the British Library. A comparison of these two paintings reveals that the former presents a rather complete scene of the opera performance with two more figures than those on the latter, indicating that the painting collected in the British Museum was produced earlier than that collected in the British Library. Though the exact period for the production of these two paintings cannot be decided since both of them might be based on a previous model, the above conclusion can still be drawn, for the former painting presents a more reliable scene opera performance compared with the latter.

Figure 2: K’ang Yin Questioning His Highness (1877, 0714, 0.823), collected in the British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Among the ten paintings, nine paintings’ titles can be traced back to the

original operas’ scenes, including Zhang Qing Gets Married, Guan Yu Slays Hua Xiong While the Wine Is Still Warm, Cui Zi Murdered the Emperor of Qi, Farewell, Concubine Yu, Tiger Slayer, Li Heiyong Lending His Troops (a misspelling of Li Keyong Lending His Troops), Dragon-Phoenix Pavilion, Shatuo Kingdom Lending Its Troops and Selling Leather Bowstrings. In addition to the above-discussed two paintings that are similar to each other,

there are other pairs of paintings that resemble one another collected in those two

locations. Some pairs are based on the same opera though they have slightly different

titles, including The Marriage of Chou Ch’ing and Zhang Qing Gets Married, Ts’ui Tzu Assassinates the Emperor of Ch’i and Cui Zi Murders the Emperor of Qi (considering the official-monarch relation between Cui Zi and the Emperor of Qi in

traditional Chinese culture, “assassinate” is more appropriate compared to “murder”

in the description of Cui Zi’s action), Farewell, My Concubine and Farewell, Concubine Yu, as well as K’e Yung Borrows Troops and Li Heiyong Lends His Troops. Tiger Slayer and Selling Leather Bowstrings are from the same scene in the same opera. Altogether, the paintings collected in

the British Library and the British Museum were drawn based on 39 scenes from Chinese

operas.

The painters of these paintings are unknown. Some people mentioned some painters that were active in Guangzhou. For instance, in John Reeves’s notes, he mentioned four outstanding painters he hired to draw flora and fauna in the Lingnan area, including Akut, Akam, Akew, and

Asung [14] that should be transliterations starting with the pinyin “A”; in line with Crossman’s research, possible painters who were active in Guangzhou in the early 19th century include Spoilum, Cinqua, Pu Qua, Foeiqua, Lamqua, Mayhing, Hing Qua, etc. [15] Some of these painters might have created some of the paintings discussed above, but they cannot be credited since the current academia knows little of them.

2. A Case Study: While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father

In this part, I will take While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father as a case to explore how these Chinese export paintings can be valuable sources for the investigation of Chinese operas.

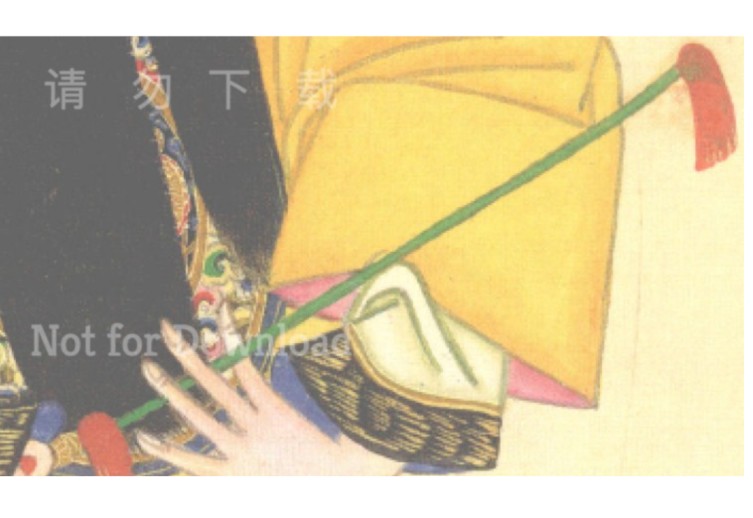

Figure 3: While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father (c), collected in the British Library. The British Library Board (Add. Or. 2069)

While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father, also called Returning from Hunting or Returning from Hunting to Inquire the Father, was a scene from A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey, a southern Chinese opera. As can be seen in Picture 3, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father depicts such a scene: on the left of the painting, the young boy named Young Yaoqi,

facing the audience squarely from his left side, stood in front of a couple; with

a letter in his hand and doubt on his face, he

[14] The notes are collected in the Natural History Museum in London. See Liu. Fengxia, The Port Culture: A Glimpse of the Modern Communication between China and the West through Guangdong’s Export Art, p.128. note 36.

[15] Crossman, Carl L. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade – Paintings, Furnishings and Exotic Curiosities, p.406.

seemed to be asking the couple something. It told a story relevant to the boy’s biological mother. Young Yaoqi bumped into his biological mother Li Sanniang who was drawing water at the well while he was hunting for a white rabbit. After this stranger told him her ex-husband’s and her son’s names, he suddenly had a sense of doubt, for they were the same as his father’s and his names. Therefore, he went back home immediately to interrogate his parents about the issue with a letter given by Li Sanniang. Next to Young Yaoqi laid his horsewhip and spear carelessly, indicating that he might have rushed to his parents to inquire about his biological mother that he did not have time to take off his hunting attire and get his horsewhip and spear in order, for usually they should have been taken backstage by his servant in the opera. On the right of the painting was Liu Zhiyuan who joined the army after parting with his ex-wife Li Sanniang. Luckily, he won the favor of the ambassador Yue who got him to marry his daughter; and later, he was promoted to the Conciliator of Jiu Zhou, or nine areas in the provincial level where the Han Chinese inhabited. Staring at Young Yaoqi, he looked astonished and seemed to wait for his son to show him the letter. On the left of Liu Zhiyuan sat Mrs. Yue who looked elegant and chaste. The painting may depict the scene when Young Yaoqi was handing over the letter to Liu Zhiyuan after he finished singing “Halt the Horse to Harken” and told him about his experience of meeting Li Sanniang unexpectedly.

2.1 Opera Scripts Relevant to Scenes in Export Paintings

2.1.1 Plots and Characters

The story of A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey can be dated back to Stories on the History of the Han Dynasty with Commentaries from Stories on the History of the Five Dynasties with Commentaries, an anthology of historical accounts by an anonymous author in the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Yet, there are no plots such as Young Yaoqi meeting his biological mother unexpectedly while chasing a rabbit or returning home to question his father with the letter in it. [16] Similar plots can also be found in the remaining five fragments from the twelve plays of Liu Zhiyuan’s Story Told in Zhugongdiao-Style Song in the Song and Jin Dynasties. [17] Another related script was Li Sanniang Holds the Seal in the Hemp Field, a Zaju by Liu Tangqing, in the Yuan Dynasty, but its script was lost.

As of now, there are three versions of the complete edition of A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey available. The first is the Fuchuntang edition in the Ming Dynasty by the Tang family in Jinling under Emperor Wanli’s reign (1572-1620) and it was published with the title of A New Edition of Liu Zhiyuan and A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey with Woodcut Illustrations and Footnotes on Diction; the second is the Jiguge version in the Ming Dynasty by the Mao family and it was published under the title of The Finalized Manuscript of A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey with Quality Illustrations [18]; the third one is the Beijing Yongshuntang edition from the Chenghua period in the Ming Dynasty and it was published with the title of A New Compilation of Liu Zhiyuan’s Homecoming and A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey. [19] In the second and third editions, nowhere can be found plots narrating Li Sanniang writing a letter to Liu Zhiyuan and Young Yaoqi returning home to interrogate his father with a letter given by Li Sanniang; in addition to that, concerning the plot when Liu Zhiyuan told his son who his biological mother was, Mrs. Yue was not with them. Therefore, these depictions in the two opera editions cannot match with those in the painting. Comparably, the plots narrated in the Fuchuntang edition matched with the content in the painting.

There are also other versions of operas pertinent to the painting. An abridged Jinxiantang edition in the Ming Dynasty under the reign of Jiajing was circulated under a possible title of Liu Zhiyuan, Selected Plays of Ancient Chinese Drama, [20] which includes the plot that Li Sanniang wrote a letter to Liu Zhiyuan but the plot that Young Yao interrogated his father with the letter was not selected. Resembling those plots in the Jiguge and Yongshuntang editions are the Returning from Hunting collected in The Score of Ink-Colored Snow [21] and The Accessorized White Fox Hide [22], both of which are anthologies of opera highlights popular in the Ming and Qing Dynasties; the six versions of Returning from Hunting [23] in the Shengpingshu opera scripts from the southern mansion of Qing palace collected in the National Library of China and the Palace Museum; and The Complete Sequence of Returning Home from Hunting [24], a Kunqiang, collected in Chewang mansion.

[16] A New Edition of Tales from the Five Dynasties, Chinese Classic Literature Publishing House, 1954.

[17] See Zhu, Pingchu. The Comprehensive Guide to Variegated Modal Tunes, Gansu People’s Press, 1987.

[18] For more information regarding the two editions, see Zheng, Zhenduo, ed.. The Collection of Classic Chinese Opera, Volume 1, in the anthology series of The Collection of Classic Chinese Opera, The Commercial Press, 1954.

[19] The Spoken and Sung Lyrics from Chenghua Period in the Ming Dynasty, Volume 12, Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2011.

[20] See Sun, Chongtao, and Huang Shizhong, editors. Selected Plays of Ancient Chinese Drama from the Royal Library of San Lorenzo, Zhonghua Book Company, 2000.

[21] See Wang, Qiugui, editor. The Selected Plays of Chinese Drama in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Volume 4 (6), Student Book Company, 1987, 715-721.

[22] See Wang, Qiugui, editor. The Selected Plays of Chinese Drama in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Volume 5 (1), Student Book Company, 1987, 1225-1234.

[23] See National Library of China, ed.. The Archives of Shengpingshu in the Qing Dynasty Collected in the National Library of China, Zhonghua Book Company, 2011, Volume 57, pp.31547-31583; Volume 107, pp.62403-62431. See also Shengpingshu Opera Scripts from the Southern Mansion of Qing Palace Collected in The Palace Museum, Volume 23, The Palace Museum Press, 2015, pp.521-558.

[24]. See Huang, Shizhong, ed. The Complete Operas Collected in the Chewang Mansion in the Qing Dynasty, Volume 6, Guangdong People’s Publishing House, 2013, pp.707-711.

Besides these, there was the plot that Young Yaoqi returned home to interrogate his father with the letter in either Returning from Hunting to Inquire the Father from Premium Lyrics [25] or Young Yaoqi Expresses His Sentiment to His Father from Selected Songs and Lyrics [26], but neither of them included Mrs. Yue in the scene. All editions considered, the only edition that matched with the scene in the export painting is the Fuchuntang edition. Normally, researchers view the Jiguge and Yongshuntang editions as one edition system and the Fuchuntang edition as another one. [27]

2.1.2 Costumes

In this section, I would like to compare costumes present in the painting with their corresponding descriptions in the operas in the two edition systems to explore which edition system the painting belongs to through an analysis of The Guideline for Apparels [28]. This book was published in the 25th year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing and it is one of the earliest records of opera costumes worn by performers in the court during the Qing Dynasty. Since The Guideline for Apparels is a record of court opera performances in the Qing Dynasty, it therefore belongs to the Jiguge and Yongchuantang editions as the six versions of Returning from Hunting do. [29] Here I will compare costumes in the painting with the descriptions of them in The Guideline for Apparels.

| Export Painting, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father | Returning from Hunting from The Guideline for Apparels | |

| Young Yaoqi | Purple-embellished crown, pheasant tail feather, crossed collar, pink casual military robe, blue dragon-patterned long vest with hanging fringe, boots, horse whip, spear, letter | Purple-embellished crown, pheasant feather, pink casual military robe, moon white flower-patterned outfit with rows of bullion fringe, hanging sword |

| Liu Zhiyuan | Gauze cap with square wings (for officials), long beard in five strands (or black beard in three strands), cobalt blue crouching dragon-patterned robe, jade belt with a red base, boots | Gauze cap, black beard in three strands, cobalt blue outfit with scarlet flaps |

| Mrs. Yue | Phoenix coronet, red base dragon-patterned women’s robe representing the python Dan role, lake-colored overcoat, blue opera cape, black boots | Cape with broad red sleeves |

From the chart above, it can be seen that the three characters’ costumes in the painting mostly resemble corresponding descriptions in The Guideline for Apparels. However, there are still two differences between the two. The first difference lies in their different types of opera costumes. In the export painting, the opera costumes worn by Liu Zhiyuan and Mrs. Yue are robes with round collars, wide plackets open on the right side, and patterned dragons, symbolizing the python Dan roles, while in The Guideline for Apparels, Liu Zhiyuan wore a robe with scarlet flaps and Mrs. Yue a cape. In Chinese opera, python, scarlet flaps, and capes are parts of the costumes worn by roles for emperors, aristocrats, ministers, generals, high officials, and noble people. Concerning python, there are male python and female python,

[25] See Wang, Qiugui, ed.. The Selected Plays of Chinese Drama in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Volume 2 (8), Student Book Company, 1984, pp.1321-1328.

[26] See Wang, Qiugui, ed.. The Selected Plays of Chinese Drama in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Volume 1 (3), Student Book Company, 1984, pp.95-100.

[27] Yu Weiming argued that the Fuchuntang edition of A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey belongs to Story of Yaoqi, a Chuanqi, rather than another version of the Nanxi A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey; he also classified some opera highlights into the system of Chuanqi Young Yaoqi. I believe that these arguments are subject to substantiation for some opera highlights integrated contents from Jiguge, Yongshuntang and Fuchuntang editions. See A Survey of the Story of Yaoqi in Chinese Operas, Volume 24, 2000.

[28] Though debated several times, the publication date of The Guideline for Apparels was finalized in the 25th year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing. See Song, Junhua, “The Guideline for Apparels and Court Opera Performances in the Qing Dynasty.” Journal of Sun Yat-sen University, no. 4; see also Cao, Lianming, “The Guideline for Apparels and Opera Costumes and Props in the Qing Dynasty Collected in the Palace Museum.” Journal of The Palace Museum, 2014, no. 2.

[29] The earliest publication date that can be dated among the six versions was the 9th year under the reign of Daoguang (1829) that was 9 years later than that of The Guideline for Apparel. See National Library of China, ed., The Archives of Shengpingshu in the Qing Dynasty Collected in the National Library of China, Volume 57, p.31547.

both full dress worn in formal occasions; for instance, the male python was worn by emperors and officials in court. Scarlet flaps, also called “open cloak” “outstretched flaps” or “straight flaps” are casual wear by emperors, marquises, and generals. While capes are “Costumes of Jianghu” frequently present in A Record of Yangzhou Decorated Boats in the period under Emperor Qianlong’s reign as well as in The Guideline for Apparels, they are now called “shawls” including male shawls and female shawls, and they were casual wear by emperors, officials and their wives, and concubines and the latter’s wives as well at home. With this in mind, it can be seen that in the painting Liu Zhiyuan and Mrs. Yue wear full dress, while in The Guideline for Apparels they are in casual wear.

The second difference falls on the different locations where the scene was performed. In the six versions of Returning from Hunting, Jiguge edition, and Yongshuntang edition, the scene was performed at Liu Zhiyuan and Mrs. Yue’s home, therefore their costumes should be casual wear. In the Fuchuntang edition, nevertheless, it was performed at the Kaiyuan temple where Liu Zhiyuan and Mrs. Yue met Young Yaoqi; since the temple was a formal venue, it can be inferred that the couple’s costumes belong to formal wear. Through an analysis of types of the costumes and their performance locations, it can be concluded that the export painting was based on the Fuchuntang edition. Also, though the Fuchuntang edition has not been widely performed as the Jiguge and Yongshuntang editions, it was still performed in the early years under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing.

2.2 The Performing Troupe in the Painting

During the period between the 5th to 10th year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing when the painting was produced, the Guangzhou opera stage was monopolized by the so-called “Extra-Guangzhou Opera Troupes” coming from around six provinces including Gusu, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Hunan. These troupes established the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association in the 27th year under the reign of Emperor Qianlong that dominated the opera performances and it went into operation until the 12th year under Emperor Guangxu’s reign (1875-1908). [30] I argue that the scene in the painting was performed by the opera troupe from Hunan province for the following reasons.

First, among many selected operas and traditional regional operas during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, only the Xiang Opera of Hunan and Daqiang Opera of Fujian titled the scene in the painting as While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father.

Second, up until now, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father is still regularly performed among the Xiang Opera of Hunan. In A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey, a manuscript copied by Chen Jianxi in Ancient Scripts of Hunan Operas published in 1980, the scene While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father was included. [31] The scene described matched a lot with that in the painting. For instance, the description that Liu Gao (Liu Zhiyuan) required Liu Chengyou (Young Yaoqi) to see him in martial attire after hunting resembled the content in the painting that Young Yaoqi wore martial attire and threw his horsewhip and spear on the ground; also, in Chen’s edition, the plot that Young Yaoqi went home to interrogate his father about his biological mother with the letter written by Li Sanniang was the same as that in the painting, thus the Chen edition belongs to the Fuchuntang edition. In addition to that, since the Fuchuantang edition was barely circulated, the resemblance of major plots between the two editions also proved the affinity of these two editions. Undeniably, there are some inconsistencies between these two editions. For example, in the former edition, when Young Yaoqi interrogated his father about his biological mother, Mrs. Yue was absent, and the story happened in Liu’s home rather than at the temple. These resemble those descriptions in the Jiguge and Yongshuntang editions. In this scenario, it can be inferred that the Xiang opera edition is probably a combination of the two edition systems. However,

[30] For more information, see Xi, Yuqing. "Opera Troupes from Six Provinces in Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty." Journal of Sun Yat-sen University, 1963, no. 3.

[31] See Opera Studio of Hunan Province, ed. Ancient Scripts of Hunan Operas: Volume 3 of Xiang Opera, Printed for Internal Use, Changsha, 1980.

the inconsistencies cannot deny the close relation between the Xiang Opera edition and the export painting since there are varied versions of While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father within the Xiang opera edition as artists possibly had different interpretations of the original script, as manifested in the “Introduction” to the Xiang Opera edition: “Since 1953, several opera troupes have performed the scene relying on revised scripts. And since artists have different interpretations of the confused titles of the tunes in both the original and revised scripts, to finalize the script of While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father is subject to further research.”

Third, it needs to be noted that Hunan opera troupes had dominated performances in Guangzhou. According to the inscriptions on the stone monument of the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association, since the 56th year under the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1791), Hunan opera troupes had emerged as the dominating troupes in Guangzhou with a number of 23 troupes among the 53 troupes in total active in Guangzhou. Although since the 5th year under the reign of Jiaqing (1800), the Extra-Guangzhou troupes had gradually declined, Hunan opera troupes and Jiangxi opera troupes remained to be the dominant performing troupes in Guangzhou. [32] Besides, even in the time when the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association monopolized the opera performing market in Guangzhou, [33] there might be independent Hunan opera troupes performing in Guangzhou. In such a context, While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father in the export painting might most likely be a depiction of Hunan opera troupes performing the scene.

2.3 Shengqiang of While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father

As for what Shengqiang system While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father in the painting belongs to, Li Yuanhao argued that it belongs to Kunqiang since the scene appeared in Kunqiang. [34] However, I believe that Li’s argument is subject to more research since this scene might also be performed in other types of operas. When this batch of export paintings was produced in the early years under the reign of Emperor Jiaqiang, Kun opera and other forms of operas were contesting for dominating the opera performance market. Since other forms of operas won the contest, many Kun operas were also performed by troupes from these other forms of operas. Here, I would like to add two more points to illustrate that While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father in the painting falls under the category of Kunqiang.

First, as pointed out in the chart and discussed above, the costumes worn by performers in the painting resembled those described in the Kunqiang Returning form Hunting from The Guideline for Apparels.

Second, the categorization of While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father into Kunqiang [35] can be supported through an analysis of its performing troupe, Hunan opera troupe discussed previously. Regarding the opera types that the Hunan troupe performed, Ouyan Yuqian claimed that some were Kunqiang and others were Nanbeilu (Banghuang), and that the Jixiu troupe in the inscriptions on the stone monuments of Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association was performing Kunqiang. Likewise, Xian Yuqing believed that what the Hunan Jixiu troupe was performing was Kunqiang. [36] Following their similar argument, I would like to add one piece of evidence from The Mirage, a fiction published in the 9th year under the reign of Jiaqing (1804) to support the argument. In the fiction, there was a plot quoted below.

[32] The data were collected in line with inscriptions on the 12 stone monuments of Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association. For inscriptions, see Guangdong Branch of China Theater Association and Research Center on Theater of Guangdong Bureau of Cultural Affairs, ed.. A Compilation of Archival Materials of Guangdong Theater, Volume 1, 1963, pp.36-67.

[33] A Record of Watching Operas along the Pearl River by Ji Zhiliang mentioned an opera troupe named Tianfuju Troupe existing in the Gengchen year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1820). Since one of its actors Young Zhoufeng was from Hunan, it can be inferred that this troupe came from Hunan; besides, this troupe was not recorded on the stone monument of Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association. See Xi, Yuqing. Opera Troupes from Six Provinces in Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty.

[34] See Li, Yuanhao. “The Record of 18th Opera: Selected Chinese Export Paintings in the Qing Dynasty Collected in the British Library and Kun Opera.” I thank Li for sharing his article to be published.

[35] See Ouyan. Yuqian. Notes upon Reflection, The Writers Publishing House, Co., Ltd., 1959, p.245.

[36] See Xi, Yuqing. Opera Troupes from Six Provinces in Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty.

…fruits were served on plates on large tables for the audience while the extra-provincial Guihua troupe and Fushou troupe were performing operas. The father and son of the Zhongweng family were toasting the audience along with the actors and actress, while the audience was toasting them back and pinning flowers on them on behalf of Chuncai. After two soups were served and four acts of a play were performed, Biyuan and others were ordered to clean the tables and put them together to form two large ones so that the audience could sit close to each other…Fengguan, Yuguan and Sanxiu, all performers, were kowtowing again to the audience, requesting more opera orders and wines. Bian Ruyu ordered The Boisterous Banquet, Jishi ordered Falling off the Horse, and Shi Yannian ordered one act from The Monkey King Borrows the Plantain Fan Thrice, while Qingju and some others did not order again.[37]

Though this paragraph has been frequently quoted by researchers, no one pointed out that the information in the paragraph is supported by those inscriptions on the stone monuments of the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association. I argue that the Fushou troupe mentioned in this paragraph was the Hunan Fushou troupe, whose name was recorded on the Monument of the Members of the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association published in the 56th year under the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1791), Monument of Renovated Chambers of the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association published in the 10th year under the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1805), Monument of Gathering of Gods of Fortune published in the 3rd year under the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1823), and Monument of Reopening the Changgeng Association published in the 17th year under the reign of Emperor Daoguang. Sanxiu in the paragraph refers to Xie Sanxiu, who was affiliated with Hunan Taixiang troupe according to Monument of Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association published in the 45th year under Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1780). He was said to have been affiliated with Hunan Fushou troupe in The Mirage, but the double affiliations did not discount the argument concerning the similarities because actors affiliated with the Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association often performed in different member troupes of the

[37] See The Mirage, dictated by Yuling Laoren and edited by Yushan Laoren (both of whom were from the Qing Dynasty), Guangya Publishing Co. Ltd., 1983, p.258.

Association [38]. Furthermore, the three acts performed all fall into Kun opera highlights, The Boisterous Banquet from The Peony Pavilion and Falling off the Horse from The Story of the Lute, while The Monkey King Borrows the Plantain Fan Thrice (also known as Borrowing the Fan) was a complete Kun opera highlight. In such a scenario, it can be concluded that Hunan opera troupes were performing Kunqiang, or at least Kunqiang was one type among many performed by them. Therefore, I argue that the opera present in the export painting belongs to Kunqiang.

2.4 Costumes and Props

The opera costumes and props during the dynasties under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s regions were recorded in detail in “Outfits of Jianghu” from Travelling Records of Yangzhou published in the Qianlong Dynasty and in The Guideline for Apparels published in the Jiaqing Dynasty. In addition to these records, the batch of the export paintings produced in the early years under Emperor Jiaqing’s reign can be a critical source for an exploration of how opera costumes and props have evolved.

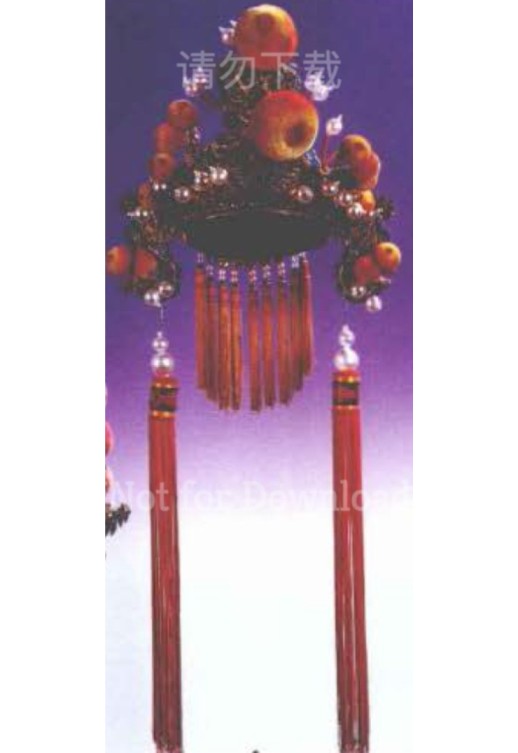

I will now discuss how the costumes and props in While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father analyzed in the previous chart have developed since then. In the export painting, the purple-embellished crown worn by Young Yaoqi was simple with only two pom-poms in its front; comparably, tassels were added to the drag tail ear-shaped beaded drops on both sides of the crown present in the palace performance paintings produced during Emperor Xianfeng’s reign (1850-1861) and Emperor Tongzhi’s reign (1861-1875). Besides, the pheasant feathers and other accessories were also refined. Although they seemed to be sumptuous in palace performance, they still looked simple in general. But the crown used for today's opera performance looked sophisticated with plenty of pom-poms and waxed white beads covering up the headpiece (see pictures 4, 5, 6). Also, in the painting, the phoenix coronet worn by Mrs. Yue was without much adornment; in contrast, at the end of Qing Dynasty, the palace-style phoenix coronet with stringed beads, colored butterfly accessories, and tassels were very delicate and luxurious. A layer of gold lacquer was applied to the base decorated with etched glass beads and the iridescent blue feathers of kingfisher were used as an inlay for coloring and miniature phoenix for ornament; in the center of the coronet was a large luminous glass bead connected to

[38] For more information regarding actors performing in affiliation with different troupes, see Huang, Wei. “A History of Extra-Guangzhou Opera Troupes: An Analysis of Inscriptions on the Stone Monuments of Extra-Guangzhou Pear Theater Association.” Chinese Theatre Arts, 2010, no. 3.

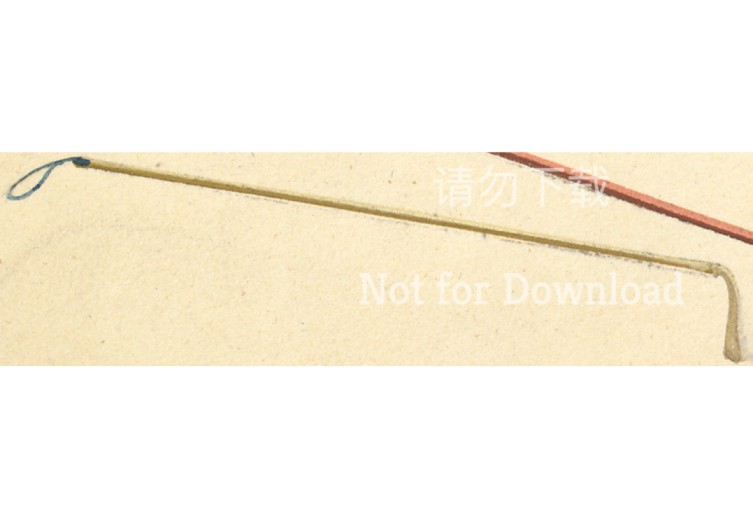

more patterned beads and flowers around it; on the back of the coronet, there were glass ornaments in the shape of blossoms and colorful tassels; the coronet’s front was decorated with standing phoenixes holding stringed beads in their beaks, with yellow, pink, and green ribbons placed along stringed beads and bullion fringes dropped down from both sides [39]. As for coronets used today, they inherited such types of coronets with rich ornaments and sophisticated designs from the Qing Dynasty (see Pictures 7, 8, 9). Another part worth a critical analysis was the horsewhip. In the export painting, it only had a single bundle of tassels on its head and a small loop on its tail; in the palace performance paintings during the dynasties under Emperor Xianfeng and Emperor Tongzhi’s reigns, the horsewhip was equipped with a handle and a lacquered rod, resembling that in the painting; in the paintings produced under Emperor’s Guangxu’s reign, colored tassels were added to the rod; for today, the tassels become even lengthier and more impressive, and two clusters of bouncy colored ribbons are added on the top of the horsewhip (see pictures 10, 11, 12, 13). Based on the above analysis, it can be seen that from the period under Emperor Qianlong’s and Emperor Jiaqing’s reigns to the late Qing Dynasty, the styles of opera costumes and apparels have evolved “from simplicity to sophistication” that was inherited by today’s opera costumes and apparels, usually with more ornaments on them [40].

|

|

[39] See Zhang, Shuxian, ed.. The Theater Artifacts from the Qing Dynasty, Shanghai: Shanghai Technology Publishing House; Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, 2008, p.216.

[40] The difference between the simple costumes and props present in the export paintings in the dynasty under Emperor Jiaqing’s reign and those with plenty of ornaments is not due to the different style of the costumes and props between the civil society and the court, which can be proved through an analysis of the similarities of costumes and props present in One Warrior’s Combat from Painting of Emperor Kangxi’s Southern Inspection Tour in the Qing Dynasty and those in the export painting One Man’s Combat collected in the British Library. A comparison of the two paintings reveals that the simple style of the costumes and props in the dynasties under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s reigns was inherited from that in the dynasty under Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1661-1722). For more information on the two paintings, see The Palace Museum, ed.. Paintings of Qing Palace Performance Collected in The Palace Museum, Cultural Relics Press, 1992, p.70 and Wang, Ciceng et al. Selected Chinese Export Paintings of the Qing Dynasty in British Library (Volume 1), p.46.

[41] The picture is cited from Wang, Wenzhang, ed.. The Costumes and Props of Shengpingshu in the Qing Dynasty Collected in Chinese National Academy of Arts, The Academe Publishing House, 2008, p.124.

[42] The picture is cited from Liu, Yuemei. Wardrobe of Chinese Kun Opera, Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House, 2010, p.102.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[43] The picture is cited from Zhang, Shuxian, ed.. The Theater Artifacts from the Qing Dynasty, p.216.

[44] The picture is cited from Liu, Yuemei. Wardrobe of Chinese Kun Opera, p.113.

[45] The picture is cited from Wang, Wenzhang, ed.. The Costumes and Apparels of Shengpingshu in the Qing Dynasty Collected in Chinese National Academy of Arts, p.42.

3. Conclusion

This article explores the basic information of 46 Chinese export paintings collected in the British Museum and the British Library that were based on 39 Chinese operas. With the painting While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father as an example, it discusses its value for researching the history of Chinese operas through an analysis of its corresponding opera script version, opera troupe, Shengqiang, costumes and props. By tracing the Fuchuntang edition of A Legend behind the Rabbit Hunting Journey, Kun opera While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father performed by the Hunan troupe in the export painting, and Xiang opera While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father, this paper reveals their significance on the investigation of While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father, the history of Xiang opera and the history of Guangdong opera. Costumes and props depicted in some paintings such as the purple-embellished crown, the phoenix coronet, and horsewhip used during the dynasties under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s reigns are reliable sources for the investigation of opera costumes and props during that period. Also, the comparison of costumes and props between those in the painting and those in the Qing opera paintings and opera costumes shows that the style of opera costumes and props evolved “from simplicity to sophistication” since the period under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s reigns, which offered references for the research and design of opera’s costumes and props.

In general, this batch of Chinese export paintings was produced in the early years under Emperor Jiaqing’s reign. Other forms of paintings in the Qing Dynasty displaying stage opera

[46] The picture is cited from Zhang, Shuxian, ed.. The Theater Artifacts from the Qing Dynasty, p.233.

[47] The picture is cited from Liu, Yuemei. Wardrobe of Chinese Kun Opera, p.159.

performances include opera paintings in the court of Qing and opera-themed New Year paintings produced in the later period. For instance, Operatic Painting Album and Operatic Painting Albums of People in the Qing Dynasty were produced no earlier than the 11th year under the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1861), or in the mid- or late-period under Emperor Guangxu’s reign as contended by Zhu Hao. In terms of the New Year paintings, although they had been produced early, the type of them that fully represent opera stage performances without such contents as buildings, pavilions, hills, water landscapes, horses, or carts was produced in the period under Emperor Daoguang’s reign (1821-1850). Also, adopting western painting techniques such as perspectives as well as light and shadow, these export paintings displayed more realistic opera performances especially in light of its spatialization of stage performances compared with those performances in other kinds of theater-themed paintings. Furthermore, these export paintings covered varied opera elements, incorporating operas from both “Huabu and Yabu.” With these characteristics, these paintings can be helpful in disseminating Chinese operas abroad and promoting cultural communication between China and the rest of the world. It needs to be noted that many plays of Kun operas present in these paintings represent the “Kun Opera Tradition under Emperor Qianlong and Emperor Jiaqing’s Reigns.” It has been viewed as the standard Kun opera performance and is still a hot research topic in the current academic community. All in all, these theater-themed Chinese export paintings are an invaluable source for research and deserve further exploration.

[48] See Zhu, Jiajin. “Brief Two.” in Liu, Zhanwen, ed..The Archives and Illustrations of Theater Collected by Mei Lanfang, Hebei Education Publishing House, 2001.

[49] See Zhu, Hao. “The Periodization of Opera Performers in the Qing Palace.” Screen and Stage Review, 2015.

[50] See Zhu, Hao. “The Theater-Themed New Year Paintings Were Produced No Earlier Than the Mid Qing Dynasty: On the Problematic Periodization of in the Volume Shanxi and Volume Gansu in A Record of Chinese Theater Series.” Cultural Relics, 2016, no. 5.

This article was published in Chinese in 2020.

Chen, Yaxin. "A Preliminary Exploration of the Early 19th Century Chinese Export Paintings Collected in Britain: While Delivering the Answer He Meets His Father as a Case Study". Chinese Theatre Arts, vol. 4, 2020, pp. 106-113.

Translator 1: Gang Hu, Binghamton University

Translator 2: Fan Yang, Binghamton University

Translator 3: Hailing Lyu, Binghamton University

Translator 4: Yunsong Luo, Binghamton University

Translator 5: Yangzhou Bian, Binghamton University

Proofreader: Emily Rosman, Binghamton University