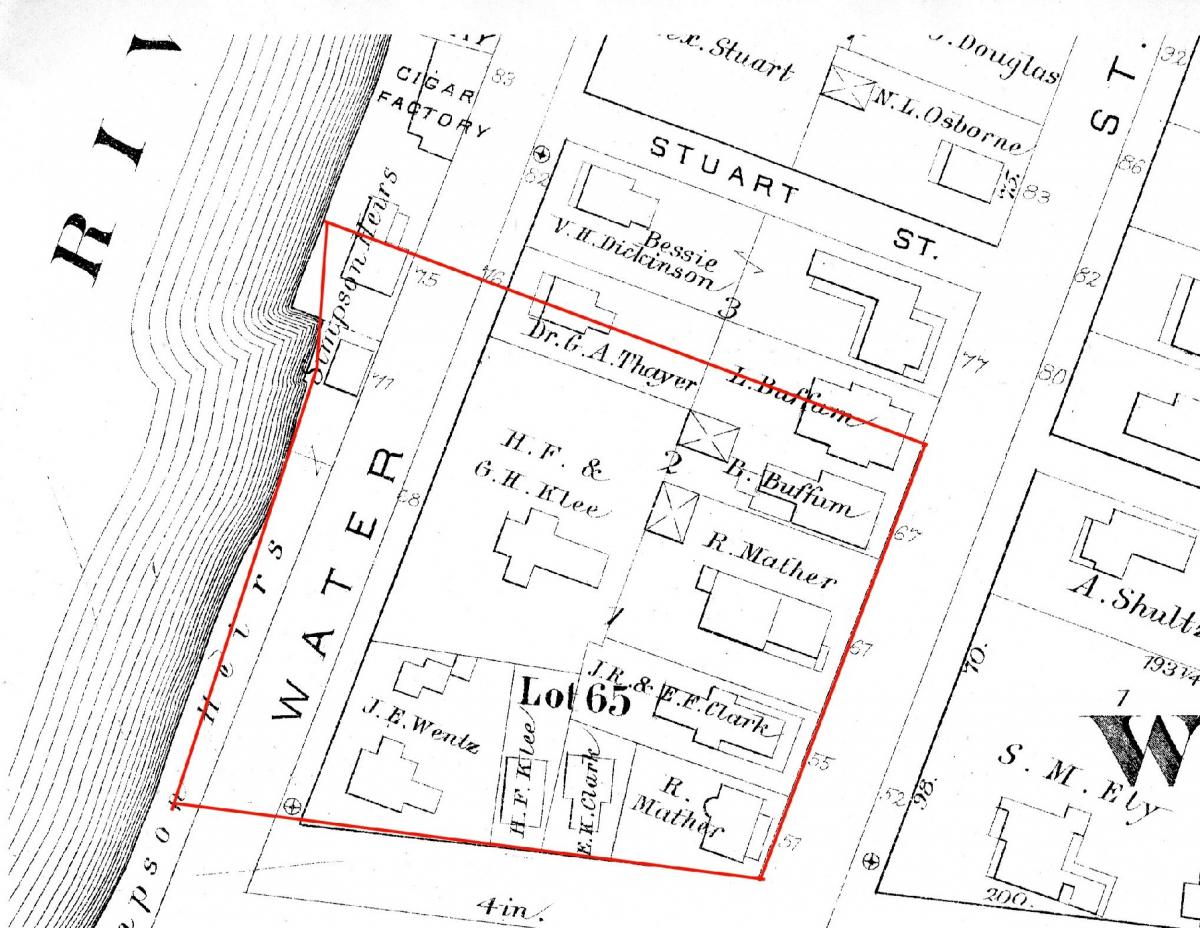

The Downtown Academic Center project block is situated within one of the early sections of the city. Early settlement focused on Court Street, which became the main commercial street, and the perpendicular Water Street, which ran along the Chenango River. The project area was principally used for residential purposes during the 19th and early 20 centuries. Residential development of the area intensified during the second th half of the 19th century and several of the original lots were subdivided. In the 20th century, the block experienced commercial development along Water Street and Susquehanna Street, including the MacDonald drug factory, the Blind Workshop building (AVRE), which eventually encompassed the MacDonald factory, used car dealerships, a factory building that was occupied by Link Aviation for a period, and other commercial buildings. All of the residential and commercial/factory buildings were removed during urban renewal in the late 1960s and early 1970s except the Blind Workshop/AVRE building, which was still standing in 2007. The remainder of the block was converted into an asphalt parking lot.

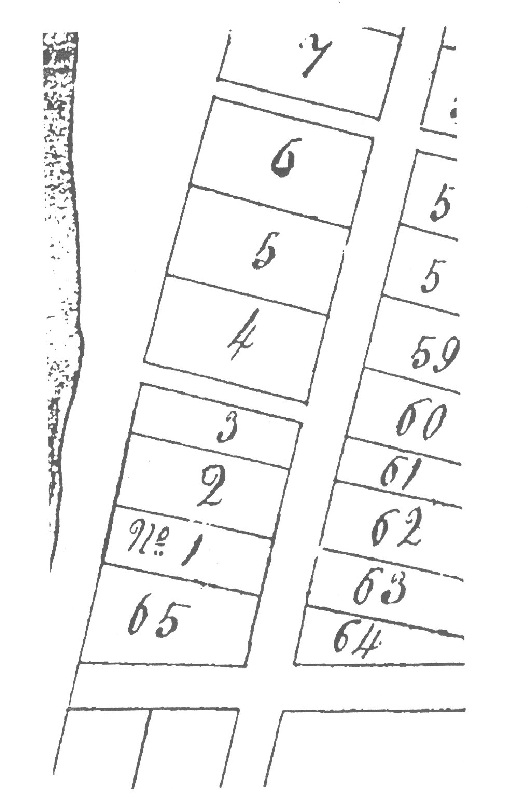

A request by Bingham to survey and plat the area for the village of Chenango Point/Binghamton resulted in an 1811 map that shows the outlines of the original block lots. The project area is depicted on this map as bounded by Second Street (Washington Street)and Susquehanna Streets and the Chenango River. The map shows Whitney's original lot division of the project area, made up of four original lots.

As the block developed, it became a residential area primarily occupied by native born, wealthy families. Residents of the project area during the first three-quarters of the mid 19th century included merchants, professionals, and manufacturers. Influential families occupying the block included county treasurer Richard Mather, Deputy County Clerk John T. Doubleday, flour mill owner Hiram Myer, and lawyer Daniel S. Dickinson. Family ties linked several of the households within the project area, as well. For example, Mason Whiting, a lawyer and prominent early settler from a distinguished New England background, seemed to have an endless supply of daughters who attracted residents and property owners on this block. Richard Mather, Henry Mather and John T. Doubleday were all brothers-in-law, married to daughters of Whiting. The Mathers and the Doubledays all became prominent, wealthy citizens of Binghamton.

Despite the elite character of the block in this period, the project area was somewhat mixed. In the early to mid 19th century, there were two artisan families who lived within the project area. Both were located along Water Street and this would have been the less visible side of the block. William Wentz was a cooper and Daniel Simpson, who began his residence on the block in 1862, was a tanner/currier. Both Wentz and Richard Mather rented properties on the block to middle class artisans and laborers. By the late 19th century, renters were primarily working class. The artisan and laborer residents were somewhat marginalized on the edges of this residential area but would still have been hard to ignore within the daily life of the block.

Equally hard to ignore was the increasingly industrial setting of the area directly to the south of this block. For much of the 19th century, Washington Street to the north of Susquehanna Street was a generally elite residential setting that featured the homes of some of Binghamton's merchants, manufacturers, and politicians before it graded into the commercial district at Court Street. The quadrant defined by Susquehanna and Washington Streets and the canal directly southeast of the project area featured a tannery, cooper, pottery, and dry dock, among other industries.

Despite the adjacent industrial development, the composition of the block did not experience major changes until the late 19th century. The first immigrant, working class residents on the block were the Klee family, who purchased a house lot from William Wentz along Susquehanna Street in 1867. By the beginning of the 20th century, the transition of the block to immigrant, working class housing was already underway. The Mather and Doubleday houses were both converted into apartments in the early 20th century and the occupations of residents included cigar makers, plumbers, "moulders", shoemakers, machine operators, and others. As suburbanization progressed and the block lost its aura of exclusive residential precinct, manufacturing and commercial ventures took over the area. Soon the houses were replaced by a patent medicine factory, auto sales and service building, and other commercial structures. By the middle of the 20th century, only four of the fourteen houses that are present in the project area on the 1885 map were present and these were all being used as apartment buildings. The surrounding area was largely commercial and industrial and included a factory for the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company on the old Weed Tannery property, as well as various other shops and manufacturers. The remaining houses were all removed by the Binghamton Urban Renewal agency in the late 1960s and early 1970s.