Archaeological investigations at the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site discovered sheet midden deposits from two periods of occupation during the early to mid-19th century. The main deposits relate to the site's association with the Hickory Grove Estate, which belonged to Abraham Van Anden and the Van Anden family from c. 1801 until 1854. The second main period of deposition is related to the site's association with the Rosenlund Estate owned by Edward Bech and his wife until 1905. The materials recovered from the deposits show a pattern of 19th century domestic activities.

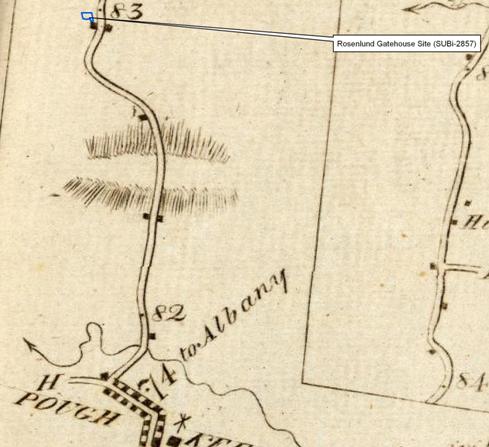

After analysis, archaeologists proposed that the materials recovered from the Rosenlund Gatehouse site were probably associated primarily with an early residence built by the Van Anden family. In 1836, the Van Anden family constructed a Greek Revival house as their main residence. This structure was not related to the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site. The 1789 map suggests the presence of an earlier residence that was in the area of the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site. The early house was positioned close to the New York to Albany Post Road (US 9). This would have allowed easy access for transport to the nearby Village of Poughkeepsie or larger cities. It would also have allowed easy access for visitors. These same characteristics probably made it a prime location for the Rosenlund Gatehouse. The area between the post road and the Hudson River were probably used as farm fields until the construction of the main house in 1836. The remains of the Van Anden's residence are limited to the sheet midden, which is concentrated in the southern section of the Rosenlund Gatehouse. There is no foundation to associate with the sheet midden, and the presence of the gatehouse may have removed earlier deposits. Therefore, it is difficult to determine if this is the full extent of the Van Anden sheet midden or if there was a larger sheet midden that exhibits a different overall depositional pattern and context.

The Van Anden household was involved in a rapidly changing world. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the new American nation faced a philosophical division on how it would progress. This division was political, economic, and social and would define the nation's growth for the rest of the 19th century. It was primarily associated with a debate between Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans and Alexander Hamilton's Federalists. Jefferson pushed for a nation founded in agrarian economics, while Hamilton pushed for the development of an industrial economy. Poughkeepsie was at the forefront of this ideological struggle. The Village of Poughkeepsie would change into the City of Poughkeepsie based on the development of trade and industrialism across the Hudson Valley. At the edge of the village, farms, like the Van Anden's Hickory Grove, had to respond to the new demands of a new market economy based on the needs of rising industrialism.

Jefferson adopted the ideas of John Locke for his republican ideology and attempted to promote the idea of the self-reliant farmer. For Jefferson, government's role was to develop equitable relations between workers and owners. It was the job of government to arbitrate grievances between the two groups (Shackel 1996). As a result, individual citizens were expected and did expect to take an active role in community and government interests. Jefferson saw industrialism as a threat to such an interactive government. Agriculture could maintain such an independence since farmers owned their own capital (farmsteads) while industrial workers were reliant on mill and factory owners.

In opposition to Jefferson, Hamilton pushed for the development of an industrial economy based on the philosophies of Thomas Hobbes. Where Locke saw humanity as peaceful in nature, Hobbes saw humanity as innately violent and competitive. Only with the formation of centralized government institutions could peace and stability be attained. Hobbes saw industrialism as developing new technologies, markets, and goods that would benefit the average citizen as well as farmers (Shackel 1996). For Hobbes, the joining of the social contract and enjoying stability came at the sacrifice of certain rights. Hamilton saw that America's economic independence required the sacrifices required of industrial production.

The Jeffersonian notion of a republic founded on the self-reliant agriculturalists was more of an ideal than a reality. From its inception, the new republic saw the start of a thriving rural industrialism as entrepreneurs built mills and factories along creeks, rivers, and streams. The positioning of these mills and factories was a move toward centralization. Mill workers had to move to the factories for work rather than independently start a factory. The development of industrial manufacturing in the new republic altered the basic community relationships of rural America. Whereas farm labor was often composed of family members and some hired laborers from the local community, manufacturing plants brought in workers from outside the community, as with the textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts (Mrozowski et al. 1996). Mills and factories began to define the organization of space and community in towns outside of the traditional layouts defined by agricultural settlement. Most importantly, divisions of labor and production developed. Large farms and plantations had defined divisions between laborers and owners, but smaller family farmsteads had less stringent divisions. Mills and factories had strict division between owners, managers, and laborers.

Although at odds, the ideas of Jefferson and Hamilton both required a major shift in ideology. They both required the recognition of the self. Prior to the 18th century, most colonial Americans viewed themselves more in terms of related to the community rather than as individuals. Much of this was due to religious practice present across the colonies, but most notably in New England. During the late 17th and 18th centuries, an increased secularism pushed people to self-recognize as individuals in what many scholars see as the development of a modern worldview (Deetz 1996). The adoption of the idea of an independent self-influenced the philosophical ideas of Locke and Hobbes and in turn Jefferson and Hamilton, setting the stage for the American Revolution.

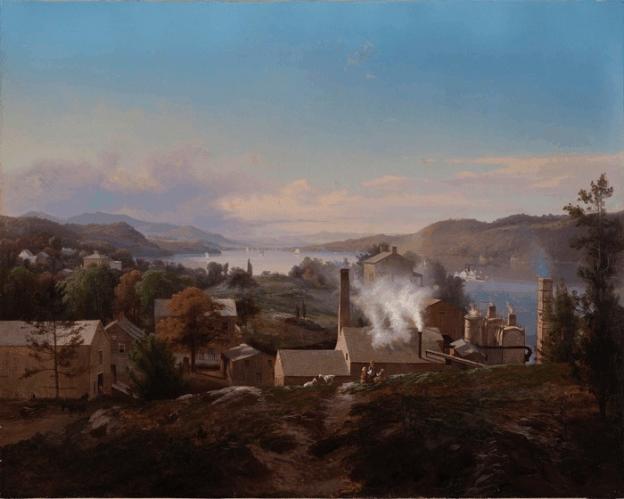

The Van Anden household at Hickory Grove was entangled in the changing socio-economic conditions of the new nation in the early 19th century. The Van Andens could visualize the development of industrialism replacing agriculture as their farmstead was located outside of the Village of Poughkeepsie. They could see the development of factories and mills along the Hudson River. They could also see the village increase in size as it turned into a city. As farmers they had to merge into the cash economy and participate in a market that went beyond the local community to outside areas. The material culture related to the Van Anden household suggests that they actively engaged with the larger market economy.

Their ceramic wares show that they were not elites, but were probably an upper middle class farming household. They purchased creamwares, pearlwares, and whitewares at times it would have been fashionable to own these types of wares, showing some ability to afford them. However, the absence of porcelain vessels suggests they did not have the means to afford the more expensive wares. The ironstone vessels also come from the later period of ironstones, the late 19th century, when mass production techniques allowed ironstone to drop in price and become more affordable.

Clothing and personal items show a level of interaction on the part of the Van Anden household with a market economy. Much of the household's clothing could have been crafted at home. However, the number and variation of buttons shows that some acquisition of goods outside of the household was needed for household clothing production. Sixteen buttons were recovered from the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site. A couple of these, including one bone and one wooden button, could have been produced within the Van Anden household. However, the other 14 buttons were produced from materials (iron, porcelain, and brass) obtained outside of the household- manufactured with mass production techniques. The smoking pipe fragments recovered from the site also show active engagement with a market economy. Although these pipes were inexpensive, they were produced on a mass scale outside of households. The porcelain doll toys, watch parts, and jewelry items further show the Van Anden's were actively consuming items from a market economy. The seven coins (one Spanish Real and six pennies) directly show a monetary involvement with a market economy. The clustering of these coins in one part of the sheet midden may suggest a possible cache or hoarding, but it is indirect and indefinite evidence for such a practice.

The Van Anden household was directly involved in a market economy, but the market economy did not fully structure the household's practices. The Van Anden's appear to have strategically accessed the larger market economy based on their needs, while still providing for household needs based on household production when applicable. This is most evident in the faunal remains recovered from the site.

The faunal remains from the Van Anden's sheet midden deposits show a strategy of mixed household production and market consumption. The identified species from the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site are all related to domesticated animals (chicken, pig, cattle). Besides an eastern gray squirrel that was most likely an intrusion, there is no evidence of hunting or the consumption of wild game by the Van Anden household. Rather, their meat consumption was based on livestock. The types of meat cuts present on the faunal remains suggest that the slaughtering and butchering of the livestock occurred on the Van Anden farmstead. Twenty-seven bone fragments had saw or cut marks that could not be identified as to a specific meat cut. This is suggestive of non-professional butchering and meat processing, which was probably done by members of the Van Anden farmstead rather than purchased from a professional butcher. The presence of oyster and clam shell does show that the Van Andens purchased some food from market sources.

Some of the ceramic vessels may provide evidence of market engagement as well. The majority of refined earthenwares, such as whitewares and pearlwares, were produced in England during the early 19th century, showing an extensive economic network with which the Van Anden household was involved. Whereas a local economy with goods produced locally could rely on noncash exchanges, such as bartering, the purchase of imported ceramics most likely required monetary resources. Yet, the redware and stoneware vessels that were also present in the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site assemblage were most likely produced locally or regionally and as such could have been acquired with nonmonetary exchanges. The Van Andens may have practiced an economic strategy common among many early Americans of placing monetary investment into ceramic vessels that would be visible to guests and visitors, while being less extravagant on vessels that would be hidden in the kitchen from public view. A pearlware vessel would be impressive or seen as basic to an upper middle class guest during a dinner or tea, but the Van Andens could use a less expensive redware or stoneware vessel in the kitchen where the guest would be less likely to see the preparation of the meal.

The transition of the farmstead from Hickory Grove to the Rosenlund estate led to a new type of farmstead and a new household with new relations with the market economy. Edward Bech was heavily involved in the market economy. As an industrialist, his production centered on his iron ore mining and processing as well as his other business interests. His income was not developed from farming activities on the Rosenlund estate. For Bech, the estate was a domestic respite from his industrial activities, not a production center. The coachman that occupied the gatehouse during the site's association with the Rosenlund estate most likely did not rely on household production for goods. Instead, the coachman was involved in the market economy by working as a wage laborer for the Bechs. The estate allowed Bech to fit into the upper class estate community present along the Hudson River.

During the 20th century, the industrial and urban development of Poughkeepsie altered much of the landscape surrounding the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site and the campus of Marist College. The former farmlands became commercial and industrial areas. The commodity value of land around Poughkeepsie was no longer agricultural space, food and crops could be acquired from elsewhere even on a national and later international scale. The value was in creating space for commercial, industrial, and residential development. The Marist Brothers ownership of the former Rosenlund Estate allowed a protection for the estate's landscape to the present day.

The history of the Rosenlund Gatehouse Site has showed changing relations to the surrounding market economy. The material culture present on the site illustrates how occupants reacted to the rise and continuation of the industrial and market economy that developed across the nation and more specifically in Poughkeepsie. The Van Andens faced not only a new political structure with the start of the American Republic; they had to strategize their household production and consumption activities to meet the changing economy of the new nation. As politicians, such as Jefferson and Hamilton, debated and enacted policies that pushed Americans to be either agriculturally or industrially focused, the Van Anden household had to decide what products they could produce for themselves and for sale on their farm, and what items they needed to purchase. Such decisions determined how involved in the market economy they were. It appears the Van Anden's took a mixed approach, producing what they could, but also enough surpluses on the farm to be able to purchase the material items required to participate in an upper middle class rural lifestyle. The Bech's, however, successfully engaged with the market economy, developing their income from industrial business rather than agriculture. With the Marist brothers' ownership, the site was neither industrial nor agricultural, transforming to an educational economy.